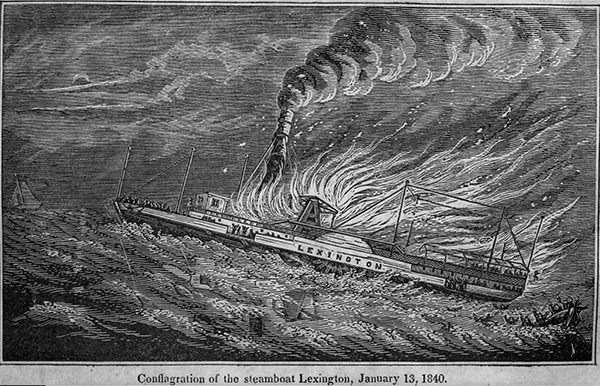

Lexington Steamship Fire Becomes Worst Disaster:

Only Four Survivors

During the 19th century, many steamships crossed between ports all over the East Coast with little regard for the safety of their passengers. It would often take a tragic event or disaster to spawn public outcry for change in creating new safety regulations to protect American and foreign citizens. Many of these early regulations are still in effect today.

Although many maritime disasters in the 19th century occurred during stormy weather or may have involved the collision of boats, disasters from fire were also prevalent. One of the worst steamship disasters in history occurred when the steamship Lexington caught fire with an estimated 150 persons aboard. The disaster caused the most significant loss of life at that time in the Long Island Sound. Safety precautions were eventually implemented years later due to this tragic incident to prevent similar future disasters and protect passengers.

The Lexington was a wooden paddlewheel steamer built in 1835, over 200 feet long. Commissioned by prominent industrialist Cornelius Vanderbilt, the ship was considered one of the most luxurious steamers. She was also considered one of the fastest steamers from New York City to Boston. The Lexington was one of those paddle-wheel steamers that came into existence at a time when the evolution of the steam engine was also shaping the railroad systems of the future. By 1840, most investors were more interested in expanding the railroad system than the steamer lines, possibly causing the lack of regulations regarding safety with the dangerous route for steamers from New York Harbor to the route around Point Judith, heading near Providence, Rhode Island. To help with the operation costs, steamers like the Lexington were used to carry passengers and cargo from New York to Boston.

Tragedy Occurred Between Sheffield Island Lighthouse in Connecticut and Eaton’s Neck Light in New York

When the Lexington set sail on a cold day on January 13th, 1840, her Captain, Jake Vanderbilt, was ill at home, unable to make the trip, so veteran Captain George Child took command of the vessel loaded with passengers and a cargo of cotton bales. She set sail at about 4 p.m. from Manhattan, New York, bound for Stonington, Connecticut; the vessel was carrying about 150 passengers and about 150 cotton bales, some piled up near the smokestack. Each bale was about 4 feet long by 3 feet wide and nearly a foot and a half thick.

The temperature had plummeted to near zero when dinner was served, and the wind was gusting. The Lexington was sailing under full steam, past Eaton’s Neck Lighthouse outside New York, at about 7:00 p.m., towards Sheffield Island Lighthouse. Suddenly, a fire broke out near the single stack, setting the bales of cotton loaded nearby aflame. Although a firefighting team was quickly dispatched, they failed to extinguish the fire. As the fire prevented the crew from shutting down the boilers, the Lexington was still cruising at full speed and out of control. As a result, when full lifeboats with panicking passengers were dispatched, they capsized as soon as they hit the water, throwing everyone into the freezing waves. The first boat was sucked into the paddle wheel, killing its occupants. Captain Child had fallen into the lifeboat and was among those killed. The ropes to lower the other two boats were cut incorrectly, causing the boats to hit the water stern-first, sinking immediately. Those passengers who survived being burned to death tried jumping in the water instead and ended up perishing from exposure to the icy waters and drowning.

Pilot Stephen Manchester turned the ship toward the shore in hopes of beaching the flaming vessel. However, the drive rope controlling the rudder quickly burned through, and the engine stopped a few miles from the New York shore. With the ship out of control, it drifted northeast and away from the land toward Sheffield Island in Connecticut.

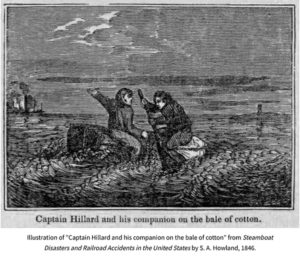

Chester Hilliard, a 24-year-old ship captain traveling as a passenger, heard the cry of “Fire!” and ran out on deck. He watched in horror as passengers jumped to their deaths in the icy waters or succumbed to the raging flames. He waited patiently for the unattended boilers to give out so the ship would finally begin to slow down about an hour later. By 8 p.m., as the ship started drifting, he persuaded a few of the remaining passengers and crew to throw themselves overboard, attaching themselves to the cotton bales that would serve as rafts, as most of the lifeboats were swamped or destroyed by fire. Many survivors were too frightened to jump into the freezing waters and stayed on board. As Hilliard and some survivors floated helplessly in the icy waters atop the bales of cotton, they watched the center of the main deck collapse, killing everyone there. About 3 a.m., as Hilliard looked at his watch, he observed the remaining hulk of the ship sink below the surface, carrying all those remaining aboard to their deaths.

Before that terrible freezing night of January 13, 1840, was over, all but four of the estimated 143 passengers and crew aboard the Lexington had perished. The many that had died would become victims of flames or icy water in Long Island Sound’s first and worst steamboat fire. Ironically, those four survivors owed their lives to the cargo of cotton bales that had fueled the fire but also served as makeshift rafts. At the time of the disaster, only one copy of the passenger list was made. This original document sank with the Lexington, thus making it impossible to verify the total number lost in the disaster.

Although the Lexington’s fire disaster was spotted along the shore of Long Island and lower Connecticut by many mariners, most boats were blocked by low tide, ice, and rough seas, hampering any rescue attempts to reach the burning steamboat. However, one ship within a few miles of the area witnessed the Lexington burning, the sloop Improvement, but the captain decided not to attempt any rescue.

The Four Survivors

Three of the four survivors were rescued by the sloop Merchant with its master, Captain Meeker, by noon the following day. Those rescued included Chester Hilliard, a passenger on board the Lexington, Captain Stephen Manchester, the Lexington‘s pilot, and Charles Smith, a fireman. All three were found frostbitten and exhausted from exposure.

Stephen Manchester, the ship’s pilot, and about 30 others huddled near the ship’s bow until around midnight, when he, with several passengers, tried to step onto a makeshift raft, which immediately sank. He then climbed onto a floating bale of cotton with a passenger named Peter McKenna. Three hours later, however, McKenna died of exposure.

Charles Smith, one of the ship’s firemen, descended the stern of the boat and clung to the rudder with four other people. Exhausted and freezing, the five jumped into the churning sea just before the ship sank around 3:00 a.m. and climbed onto a floating piece of the paddlewheel. The other four men who were with Smith died of exposure hours later.

Chester Hilliard, the only passenger to survive, had helped crew members throw bales of cotton to people in the water. He climbed onto the last bale at 8:00 p.m., along with the ship’s fireman Benjamin Cox. About eight hours later, Cox, weak from hypothermia, slipped off the bale and drowned in the freezing waters.

The fourth survivor, second mate David Crowley, drifted for 43 hours on a bale of cotton, coming ashore nearly 50 miles to the east at Baiting Hollow, Long Island. Crowley could dig into the center of the cotton bale to stay warm. He managed to stagger nearly a mile to the nearest house before collapsing. He later fully recovered and kept the bale as a souvenir until the Civil War when he donated it to be used for Union uniforms.

Aftermath: The Inquest Jury Blames the Lexington‘s Crew and Owners

The inquest jury slammed the Lexington’s crew and its owners. They felt better judgment regarding using the buckets to extinguish the fire, and better discipline on the crew to launch the lifeboats would have saved some unnecessary loss of life. The inquest jury found a fatal flaw in the ship’s design to be the primary cause of the fire. It was noted that the ship’s boilers were initially built to burn wood but were converted to burn coal in 1839. However, this conversion had not been adequately completed. Statements were made that not only did coal burn hotter than wood, but additional amounts of coal were being burned on the night of the fire because of the storm and rough seas. The jury charged that using blowers was dangerous and that passengers and flammable cotton bales were a poor combination of cargo. After the facts were presented, the jury also slammed the Captain and Pilot for disregarding the safety of the passengers in trying only to save themselves. Even though their findings were published and handed down for more safety regulations, no new safety regulations were imposed regarding passengers and flammable cargo until nearly 12 years later when the steamboat Henry Clay burned on the Hudson River.

It was found that as the Lexington was burning and could be seen for miles, the sloop Improvement, was less than five miles away and never came to the Lexington’s aid. Captain William Tirrell of the Improvement explained that he saw the burning ship but was running on a schedule and didn’t want to miss the high tide. Following his statements, there was a public outcry in the press, as lives could have been saved.

The Lexington burned for eight hours before it finally sank, causing a horrific loss of life. An unsuccessful attempt in 1842 to raise the wreck only resulted in the ship being broken apart in pieces and sinking back in 150 feet of water. Only a mass of melted silver coins, weighing about 30 pounds, was retrieved. Many still believe her hull had gold and silver, which has never been recovered.

Unfortunately, many lives were senselessly taken away due to neglect of safety regulations, but these tragic incidents paved the way for improved conditions we all enjoy today. Safety precautions were eventually implemented years later due to this sad incident to prevent similar future disasters and protect passengers. It helps to remember those who have lost their lives or made personal sacrifices so that we all have a better life.

I wish you all a safe New Year,

Allan Wood

Exploring Sheffield Island lighthouse

The Norwalk Seaport Association provides a shuttle service to Sheffield Island, where visitors can tour the lighthouse and picnic on the grounds during summer. Festivals and clambakes are also scheduled. In Norwalk, visitors can explore plenty of museums, art exhibits, and events.

Here are some of my favorite photos of Sheffield Island lighthouse.

Books to Explore

New England’s Haunted Lighthouses:

Ghostly Legends and Maritime Mysteries

Discover the mysteries of New England’s haunted lighthouses! Uncover ghostly tales of lingering keepers, victims of misfortune or local shipwrecks, lost souls, ghost ships, and more. Many of these accounts begin with actual historical events that later lead to unexplained incidents.

Immerse yourself in the tales associated with these iconic beacons!

New England’s Haunted Lighthouses:

Ghostly Legends and Maritime Mysteries

Discover the mysteries of New England’s haunted lighthouses! Uncover ghostly tales of lingering keepers, victims of misfortune or local shipwrecks, lost souls, ghost ships, and more. Many of these accounts begin with actual historical events that later lead to unexplained incidents.

Immerse yourself in the tales associated with these iconic beacons!

The Rise and Demise of the Largest Sailing Ships:

Stories of the Six and Seven-Masted Coal Schooners of New England.

In the early 1900s, New England shipbuilders constructed the world’s largest sailing ships amid social and political reforms. These giants were the ten original six-masted coal schooners and one colossal seven-masted vessel, built to carry massive quantities of coal and building supplies and measured longer than a football field! This self-published book, balanced with plenty of color and vintage images, showcases the historical accounts that followed these mighty ships.

Available also from bookstores in paperback, hardcover, and as an eBook for all devices.

Book – Lighthouses and Coastal Attractions in Southern New England: Connecticut, Rhode Island, Massachusetts

Lighthouses and Coastal Attractions of Southern New England:

Connecticut, Rhode Island, and Massachusetts.

This 300-page book provides memorable human interest stories from each of the 92 lighthouses, like the story of the Lexington steamship fire near Sheffield Island Light. You can explore plenty of indoor and outdoor coastal attractions, including whale-watching excursions, lighthouse tours, windjammer sailing tours, parks, museums, and even lighthouses where you can stay overnight. You’ll also find plenty of stories of hauntings around lighthouses.

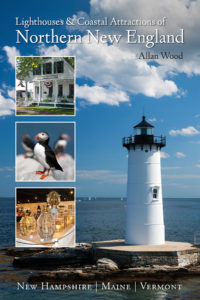

Lighthouses and Coastal Attractions of Northern New England:

New Hampshire, Maine, and Vermont.

This 300-page book provides memorable human interest stories from each of the 76 lighthouses. It also describes and provides contact info for plenty of indoor and outdoor coastal attractions and tours. These include whale watching, lighthouse tours, unique parks, museums, and lighthouses where you can stay overnight. There are also stories of haunted lighthouses in these regions.

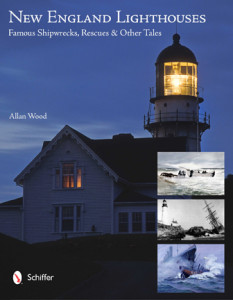

New England Lighthouses:

Famous Shipwrecks, Rescues & Other Tales

This book contains many stories, including the steamship Lexington fire near Sheffield Island Light. It is also rich in images, including vintage images provided by the Coast Guard and various organizations and paintings by six famous Coast Guard artists.

You can purchase this book and the lighthouse tourism books from the publisher Schiffer Books or in many fine bookstores such as Barnes and Noble.

Join, Learn, and Support The American Lighthouse Foundation

Copyright © Allan Wood Photography; do not reproduce without permission. All rights reserved.