The Monomoy Disaster on Cape Cod in Massachusetts

Establishment of Monomoy Life Saving Station

Monomoy Island is a large, narrow island a few miles from Chatham, considered the elbow of Cape Cod, Massachusetts. The sandy shoals around Monomoy Island are some of the most dangerous in New England, claiming many ships. Two large shoals, the Shovelful Shoal and the Handkerchief Shoal, stretch out under the water along the eastern and southern shores of Monomoy Island. Historically, Pollock Rip, an area of powerful tidal currents located off the island’s southern shore, has also caused numerous shipwrecks. These natural dangers created a desperate need for a lighthouse station to mark the area. In 1823, Monomoy Point Lighthouse was built, then rebuilt in 1855 as a 40-foot, cast-iron tower lined in brick, helping to guide shipping traffic and mariners around the constantly shifting sandbars and shoals caused by those strong tidal currents at the end of Monomoy peninsula.

As lighthouses were built as navigational aids along the shore, life-saving stations were constructed in strategic locations very near the lighthouses to house additional crew members strictly to rescue those in distress offshore. At Monomoy, these additional men were housed at the Monomoy Life Saving Station, two miles north of the lighthouse. It was one of the original nine lifesaving stations on Cape Cod. These “surfmen,” or lifeboat men, as they were called, were hired as assistants to the keeper or captain, as he was also referred to when shipping traffic and tourism were at their peak. Some also stayed on as assistants year-round to help the lighthouse keeper.

At Monomoy, the lighthouse keeper was also the lifesaving station keeper. During fair weather, his surfmen would perform drills on lifesaving techniques and maintain their equipment while patrolling the shoreline, keeping a close eye out for ships in distress. If a vessel were found wrecked on nearby ledges or sandbars, these brave men would launch their heavy lifeboat, or surfboat, into the raging sea and row through the rough surf to attempt a rescue.

All lifeboat men were known for their motto, “You have to go out, but you don’t have to come back.” These brave men would perform their trained duties in risking their lives to help stranded passengers or crew from a wrecked ship, knowing beforehand that they might perish in the sea. They were often successful, while other times, they ended up paying the ultimate sacrifice.

Monomoy Disaster Becomes Worst In History of the Life-Saving Service

Sometimes, mistakes occur in communication between stations and boats, or panic ensues when those who are rescued become too frightened, ending in tragic events. One of the worst disasters in the history of the Life-Saving Service occurred on March 17, 1902, off the southern end of Monomoy Island in the dangerous shoal called the Shovelful Shoal, located near the Monomoy Lighthouse. This tragic event involved the senseless drowning of 12 persons: five crewmen from the coal barge Wadena, and seven who were members of the lifesaving crew of Monomoy Light. The tragedy could have been avoided if proper communication had been given to the station’s keeper and those rescued had not fallen into a state of alarm on rough seas.

The events leading up to this tragedy began when a severe northeastern gale struck the area on March 11, 1902. Two barges, the Wadena, with coal cargo, and the John C. Fitzpatrick, which was being towed by the tug Sweepstakes, were heading towards Boston from Newport when they ended up being lodged on Shovelful Shoal off the southern tip of Monomoy Island. They landed about a mile away as each vessel sought shelter from the storm and a place to anchor near Hyannis on Cape Cod.

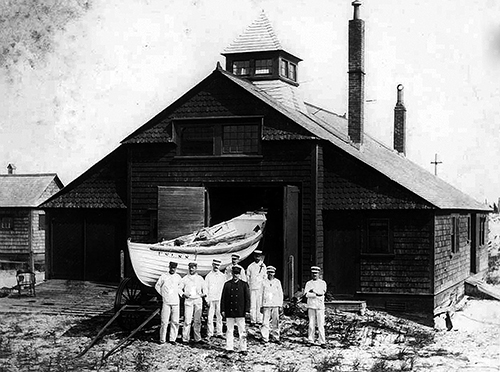

Keeper Marshall Eldridge (back row, third from left) and members of the Monomoy Lifesaving Crew, Cape Cod, Massachusetts. Courtesy The Chatham Historical Society

Captain Marshall W. Eldridge was a keeper at Monomoy Light Station, and the nearby life-saving station, with a crew of seven light station assistants, called surfmen. One of them, Captain Seth Ellis, was Keeper Eldridge’s number-one surfman and his primary assistant. Keeper Eldridge and crew members boarded both barges and tried briefly in vain to float the vessels off the shoal, but the weather made their efforts futile. The decision was made to bring crew members of each stranded barge ashore to the light station and assess the damages. When it appeared there were no signs of either vessel in danger of breaking apart, the tugboat Sweepstakes ferried crew members and employed wreckers, who were tasked with unloading some of the cargo on each barge until the vessels could float off the shoal. The tug stayed for a couple of days and was replaced by the Peter Smith, who continued the efforts of the wreckers as the Sweepstakes made port at Hyannis for needed repairs.

The wrecker crews worked tirelessly when the weather allowed them for five days until the night of March 16, when the weather became severe. Nether barge was still capable of lifting off from the shoal. The keeper had been notified that a few crew members had elected to stay aboard the Fitzpatrick to prepare to float the wreck the next day. The tug Peter Smith removed all but five people from the barge Wadena, and headed towards Hyannis Harbor. The fact that these five individuals were still on board the Wadena was not communicated to anyone at the Monomoy Light Station.

A short time later, Keeper Eldridge received a phone call from the tug captain of the Peter Smith, in Hyannis, inquiring about the remaining five men on board the Wadena. Upon hearing that there were still five men aboard the barge, and with the weather and winds worsening and creating dangerously high seas, the keeper ran down to the point and noticed a distress flag displayed off the Wadena. The keeper signaled his crew to launch the dory into the surf and headed to the barge.

Keeper Eldridge and his crew, which included Surfman Seth Ellis, made it to the barge and threw a line to be tied down by the grateful crew on the Wadena, who were quite nervous with the heaving seas and gusty winds. The Monomoy crew tried their best to position the survivors, but as they tried to turn the boat around to head away from the barge towards the shore, a huge wave crashed over the boat, filling it partially with water. Fearing for their lives, Wadena members panicked and stood up on the vessel, preventing the Monomoy lifesavers from using the oars to escape the barge. The boat could not be turned away as the Monomoy crew struggled to calm the panic of the Wadena crew. As Keeper Eldridge and his crew tried calmly to restore order, another giant wave came over the boat on its broadside and capsized it, spilling everyone into the icy waters. As the boat pitched and rolled, the five rescued crew members of the Wadena were the first to lose their grasp and perished before the Monomoy crew. Then, members of the Monomoy life-saving crew, exhausted and frozen, started to lose their hold on the capsized boat, succumbing to hyperthermia and exhaustion, and one by one, slipped away. Seth Ellis was the only one to survive and could position himself inside the water-filled boat.

Captain Elmer Mayo of the stranded Fitzpatrick, about a mile away, did not see the distress flag from the Wadena. A thick fog had rolled in that morning while he was preparing to bring his few crew of wreckers to shore from the worsening weather. As the fog lifted, he witnessed the three remaining four Monomoy crew members perish and saw Ellis in the boat. He dropped a dory overboard and was able to rescue the exhausted Ellis and bring him to shore.

Aftermath… After the Monomoy Tragedy

Monomoy Life-Saving Station after the tragedy. Seth Ellis in a dark uniform with the crew. Image courtesy of US Coast Guard.

News of the rescue and the tragedy quickly spread nationwide. Captain Mayo and Ellis received medals for bravery and the Gold Lifesaving Medal, the highest honor given for their selfless acts of courage. With the loss of Keeper Eldridge, Ellis was promoted to Keeper of Monomoy Light Station.

With such a tragic loss of life, many felt that with the Wadena remaining safe for days afterward, Keeper Eldridge and his crew’s heroic attempts were not mandated to rescue those aboard. Seth Ellis later wrote that if those being saved had conducted themselves calmly, his fellow crew members would have landed the boat safely ashore, and all would have survived the ordeal.

Before the incident, when a new life-saving station was built, the prior station was set to be removed. After the Monomoy disaster, the department continued the old station in the memorandum of Keeper Eldridge and his six men who perished.

In honor of those who had perished in 1903, the Mack Memorial was built next to the current Coast Guard Station and Monomoy lighthouse. It was erected in memory of the owner of the Wadena, William Henry Mack, who also perished, and the crew on the barge who were lost, along with the seven men of Monomoy Life-Saving Station who were drowned trying to rescue them. All the names of those who perished are inscribed, as well as the third and fourth stanzas of the poem “Crossing the Bar” by Alfred Lord Tennyson.

Viewing Monomoy Island Lighthouse

Monomoy Point Lighthouse and the life-saving station about two miles away are part of the Monomoy Wildlife Refuge, established in 1944. Boat taxis to Monomoy Island leave from the Morris Island area, and there are boat tours from the area. The most comfortable way to get a water view of the lighthouse is via the Monomoy Island Ferry, which leaves out of Stage Harbor in Chatham. They can get great closer views of the lighthouse if you go at high tide, and you can get great views of seals and other wildlife. They also provide charter walking tours led by a naturalist to hike South Monomoy Island and walk about a mile to Monomoy Lighthouse. Monomoy Island Excursions provides a waterside view of the lighthouse as part of their seal cruise if they find seals on beaches nearby.

Here are a few photos of the Monomoy Lighthouse I’ve taken.

Enjoy this unique and quiet region,

Allan Wood

Books to Explore

New England’s Haunted Lighthouses:

Ghostly Legends and Maritime Mysteries

Discover the mysteries of New England’s haunted lighthouses! Uncover ghostly tales of lingering keepers, victims of misfortune or local shipwrecks, lost souls, ghost ships, and more. Many of these accounts begin with actual historical events that later lead to unexplained incidents.

Immerse yourself in the tales associated with these iconic beacons!

The Rise and Demise of the Largest Sailing Ships:

Stories of the Six and Seven-Masted Coal Schooners of New England.

In the early 1900s, New England shipbuilders constructed the world’s largest sailing ships amid social and political reforms. These giants were the ten original six-masted coal schooners and one colossal seven-masted vessel, built to carry massive quantities of coal and building supplies and measured longer than a football field! This self-published book, balanced with plenty of color and vintage images, showcases the historical accounts that followed these mighty ships.

Available also from bookstores in paperback, hardcover, and as an eBook for all devices.

Book – Lighthouses and Coastal Attractions in Southern New England: Connecticut, Rhode Island, Massachusetts

Lighthouses and Coastal Attractions of Southern New England:

Connecticut, Rhode Island, and Massachusetts.

This 300-page book provides memorable human interest stories from each of the 92 lighthouses, like the story of the Monomoy Lifesavers tragedy at Monomoy Island on Cape Cod. You can explore plenty of indoor and outdoor coastal attractions, including whale-watching excursions, lighthouse tours, windjammer sailing tours, parks, museums, and even lighthouses where you can stay overnight. You’ll also find plenty of stories of hauntings around lighthouses.

Lighthouses and Coastal Attractions of Northern New England:

New Hampshire, Maine, and Vermont.

This 300-page book provides memorable human interest stories from each of the 76 lighthouses. It also describes and provides contact info for plenty of indoor and outdoor coastal attractions and tours. These include whale watching, lighthouse tours, unique parks, museums, and lighthouses where you can stay overnight. There are also stories of haunted lighthouses in these regions.

New England Lighthouses:

Famous Shipwrecks, Rescues & Other Tales

Over 40 stories, including the Monomoy Lifesavers tragedy on Cape Cod, are included in this image-rich book, which also contains vintage images provided by the Coast Guard and various organizations and paintings by six famous Coast Guard artists.

You can purchase this book and the lighthouse tourism books from the publisher Schiffer Books or in many fine bookstores such as Barnes and Noble.

Join, Learn, and Support The American Lighthouse Foundation

Copyright © Allan Wood Photography; do not reproduce without permission. All rights reserved.