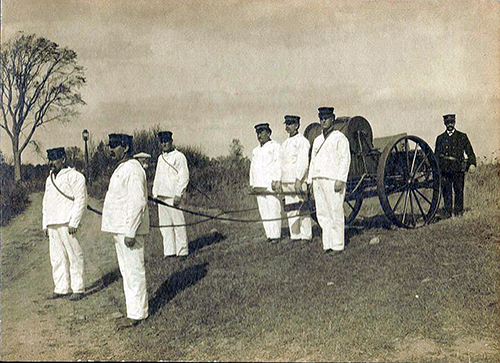

Rescue of Survivors and Between the Rescuers Themselves From Jerry’s Point Lifesaving Station Near Portsmouth Harbor Lighthouse in New Hampshire

Surfmen at Jerry’s Point Lifesaving Station carrying wagon used for rescue in New Hampshire. Image courtesy of New Castle Historical Society.

As lighthouses were built along the shore as navigational aids in guiding shipping traffic and local mariners, most buildings could only accommodate the keeper and one or two assistants. Their main objective was to keep the light burning to aid mariners in all kinds of weather. Most of the rescues by lighthouse keepers involved wrecks close to the lighthouse, where the keeper and his assistants could rescue from the shore or by a tiny lifeboat. In the mid-1800s, as shipping traffic increased along the coast, lifesaving stations were constructed in busy strategic locations near the lighthouses to house additional crew members, called surfmen, or lifeboat men. These men were highly trained in rescue efforts alone and could rescue more significant numbers of individuals than lighthouse keepers. They also used special heavy lifeboats to drive through the surf to the wreck.

Jerry’s Lifesaving Service Station is Built

By the late nineteenth century, residents along the Piscataqua River that borders the New Hampshire and southern Maine regions petitioned for a lifesaving station on New Castle Island, next to Portsmouth, New Hampshire. The island also contained Fort Constitution (also known as Fort Point), which maintained Portsmouth Harbor Lighthouse and was located across the river from Maine’s Whaleback Lighthouse. This region was extremely busy with shipping traffic coming into and out of Portsmouth, and during storms or in fog, many vessels would be wrecked along the rocky shoreline, out in the Isles of Shoals, or would get caught in the deep, strong currents of the Piscataqua River. The government granted the request and built a Lifesaving Service Station at Jerry’s Point in 1878, located on New Castle Island a few miles from Portsmouth Harbor Lighthouse. Other lifesaving stations were also built in the area and spread along the eastern coast.

Early Jerry’s Point Lifesaving Station, New Castle Island, NH, near Portsmouth Lighthouse. Image courtesy of US Coast Guard.

By 1883, nearly five years after its construction, Jerry’s Point Lifesaving Station recorded 44 instances where assistance needed to be given to stranded vessels. Keeper (Captain) Silas H. Harding and his seven surfmen rescued 16 survivors during this period. Harding was always impressed with his crew and would always make it well known of his admiration for their courage and big-heartedness for their fellow mariners and one another. He and his faithful crew had their experience and courage tested in rescuing survivors from the stranded schooner, Oliver Dyer, and bravely rescuing one another from what could have been an inevitable perilous fate. It became one of the bravest acts of heroism in the region’s lighthouse and lifesaving history.

Rescue of Crew of the Oliver Dyer, and Between Themselves

On November 25, 1888, the schooner Oliver Dyer had acquired a load of coal from Saco, Maine, and was heading to her homeport of Weehawken, New Jersey. The winds had picked during the day, and the captain set her anchor just outside the entrance to Portsmouth Harbor, about a half mile from Jerry’s Point Lifesaving station, located a short distance from Portsmouth Harbor Lighthouse. The storm increased with gale force winds, and by 1:15 A.M., on November 26, huge waves began to force the Oliver Dyer away from her haven and drag her inward towards the rocky shoreline onto the rocks. The ship’s anchor was no match for the surging waves and was dragged across the bottom as the helpless schooner moved closer to the ledges.

Visibility was still very poor while Surfman Robinson from the lifesaving station was on patrol. He would not see the stranded vessel until around 5:45 A.M., just before daybreak. By then, the Oliver Dyer lay stranded on the ledges near Jerry’s Point Lifesaving station about a few hundred yards offshore. Robinson ran back to the station to notify Keeper Harding. Harding sounded the alarm and called all hands, then he and Robinson ran down to the rocks to assess the impending danger.

At this point, the vessel had lodged itself about 75 feet from a large flat rock covered in ice, which was continuously breached by the vicious surf and gale-force winds. Harding decided to make the rescue from the rock, as it seemed the only launching point to help the survivors.

As Harding and his crew reached the rock, they saw one man had already jumped from the helpless schooner and was struggling in the icy waters. The winds blew, and the surf relentlessly washed over the stranded vessel. Surfman Hall jumped into the waves and got a firm hold of the struggling crewman. The rest of Harding’s crew began dragging the survivor and Hall towards the large ice-covered ledge. Just as Hall had reached it and was ready to lift the man onto the rock with the rest of his crew, a huge wave swept over and tumbled both men and their rescuers into the water. Luckily, they were on the shoreline side of the ledge; otherwise, they would have been swept out to sea from the ferocious undertow and drowned.

As they clung to the jagged edges of the rock, the waves receded, and the men regained their footing. Harding had also slipped and risked being swept seaward in the undertow. Surfman Randall quickly grabbed and held him tightly until he could reach the rock. All the men were bleeding from being bashed around the rocks from the undertow, with Surfman Hall receiving the worst wounds. Harding’s crew managed to climb back on the rock, while Surfman Hall and the survivor of the Oliver Dyer were quickly hauled onto the ledge and brought to the safety of the shore.

The frightened crew of the Oliver Dyer could see that the wreck would soon break up. As they witnessed the rescue of one of their comrades, one other member, the cook of the schooner, jumped into the icy waters but was caught in the undertow, preventing him from gaining distance to the shore. Surfman Randall saw the crew member struggling and jumped to rescue the exhausted survivor as he was dragged seaward by another undertow. The cook managed to hold onto Randall as both struggled to swim back towards the rock. They finally overcame the raging waves and made it to the safety of Keeper Harding’s crew.

Keeper Harding decided that the only and best method to rescue the two remaining crew members was to use the heaving stick and line he had carefully placed in the patrol box nearby the night before. After a few attempts of throwing the heaving stick, it finally reached the wreck for the other crewmen. They tied the lines around each other’s bodies under their arms as Harding persuaded the survivors to jump into the freezing waters. The men were then carefully dragged onto the rock to safety as the waves continued to wash over another member of Harding’s crew, who lost their footing and was helped up by his comrades.

Harding’s crew and the survivors were exhausted and freezing from the bitter winds. The men of the Oliver Dyer wreck were cared for at the station for two days. Harding’s men could save all crew members except for one who had washed overboard before they had reached the wreck. Keeper Harding and each man of his crew had risked their lives in not only trying to save the crew of the Oliver Dyer from their perilous position on that dangerous rock but also saved one another as each was washed over into the icy and deathly grip of the thunderous surf. All lifesavers survived without any long-term effects from their ordeal. The incident made Harding and his crew local heroes, and each received a Gold Life Saving Medal from the Carnegie Foundation for their heroic efforts.

Jerry’s Point Lifesaving Station remained in service until 1908 and was used during the war efforts. A replacement light station was built across the Piscataqua River on the opposite shore near Fort Foster on Wood Island in Kittery, Maine, near Whaleback Lighthouse. It is known today as the Wood Island Lifesaving Station but is sometimes still referred to as Jerry’s Point Lifesaving Station.

Exploring New Castle Island and Viewing Portsmouth Harbor and Whaleback Lighthouses

New Castle Island lies outside Portsmouth and is connected by Route 1B. One of the most beautiful ocean-side parks in the region is Great Island Common, within walking distance from Portsmouth Harbor lighthouse. It offers beaches, recreation, climbing rocks, and views of Portsmouth Harbor Lighthouse in New Hampshire and Whaleback Lighthouse across the river in Kittery, Maine. From one vantage point, you can get detailed views of both Portsmouth Harbor and Whaleback lighthouses from both states. You can explore Fort Constitution, and during the summer months, you may be able to climb the tower of Portsmouth Harbor lighthouse inside the fort by the Friends of Portsmouth Harbor Lighthouses (FOPHL). Be wary that you are at an active Coast Guard station, so follow all directions. Plenty of boat tours out of Portsmouth will take you by both lighthouses heading to and from the harbor.

Wood Island Life Saving Station has undergone a complete restoration and will be available as a maritime museum for historical tours.

Here are some photos of Portsmouth Harbor lighthouse.

Here are some photos of Whaleback Lighthouse across the river which you can easily view from Great Island Common Park.

Happy Holidays!

Allan Wood

Books to Explore

New England’s Haunted Lighthouses:

Ghostly Legends and Maritime Mysteries

Discover the mysteries of New England’s haunted lighthouses! Uncover ghostly tales of lingering keepers, victims of misfortune or local shipwrecks, lost souls, ghost ships, and more. Many of these accounts begin with actual historical events that later lead to unexplained incidents.

Immerse yourself in the tales associated with these iconic beacons!

The Rise and Demise of the Largest Sailing Ships:

Stories of the Six and Seven-Masted Coal Schooners of New England.

In the early 1900s, New England shipbuilders constructed the world’s largest sailing ships amid social and political reforms. These giants were the ten original six-masted coal schooners and one colossal seven-masted vessel, built to carry massive quantities of coal and building supplies and measured longer than a football field! This self-published book, balanced with plenty of color and vintage images, showcases the historical accounts that followed these mighty ships.

Available also from bookstores in paperback, hardcover, and as an eBook for all devices.

Book – Lighthouses and Coastal Attractions in Southern New England: Connecticut, Rhode Island, Massachusetts

Lighthouses and Coastal Attractions of Southern New England:

Connecticut, Rhode Island, and Massachusetts.

This 300-page book provides memorable human interest stories from each of the 92 lighthouses. You can explore plenty of indoor and outdoor coastal attractions, including whale-watching excursions, lighthouse tours, windjammer sailing tours, parks, museums, and even lighthouses where you can stay overnight. You’ll also find plenty of stories of hauntings around lighthouses.

Lighthouses and Coastal Attractions of Northern New England:

New Hampshire, Maine, and Vermont.

This 300-page book provides memorable human interest stories from each of the 76 lighthouses, such as the story of the rescue of Oliver Dyer, by Portsmouth Harbor Light in New Hampshire. It also describes and provides contact info for plenty of indoor and outdoor coastal attractions and tours. These include whale watching, lighthouse tours, unique parks, museums, and lighthouses where you can stay overnight. There are also stories of haunted lighthouses in these regions.

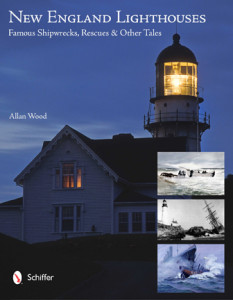

New England Lighthouses:

Famous Shipwrecks, Rescues & Other Tales

This book contains over 40 stories, including the rescue of the Oliver Dyer near Portsmouth Harbor Lighthouse on the seacoast of New Hampshire. This image-rich book also contains vintage images provided by the Coast Guard and various organizations and paintings by six famous Coast Guard artists.

You can purchase this book and the lighthouse tourism books from the publisher Schiffer Books or in many fine bookstores such as Barnes and Noble.

Copyright © Allan Wood Photography; do not reproduce without permission. All rights reserved.

Join, Learn, and Support The American Lighthouse Foundation