Wampanoag Native Americans of Gay Head (Aquinnah) Light and Nearby Life Saving Station Helped Save 21 Lives from City of Columbus Wreck

Gay Head Lighthouse on Martha’s Vineyard moved back from the edge of dangerous cliffs a few years ago. This historic beacon is about 130 feet above these cliffs on the western side of Martha’s Vineyard in Massachusetts. It was built in a region surrounded by the Wampanoag Native American tribe, where many descendants live there today as well. It lies in the town of Aquinnah and is often called “Aquinnah Light” by the locals. The lighthouse stands guard where an underwater rocky ledge known as the Devil’s Bridge reaches out from the Gay Head Cliffs, threatening ships entering Vineyard Sound and along the main shipping route to Boston Harbor from the south. The ledges were considered one of the most dangerous points in the region. They form a large cluster of submerged rocks, creating a double ledge.

The lighthouse is also famous from a historical point of view as having employed the first Native Americans to serve as volunteers at both the lighthouse and the life-saving station nearby in Chilmark. It is also famous for its personnel and involvement in rescuing survivors of the wreck of the City of Columbus, one of New England’s worst disasters in the late 1800s.

In 1884, Keeper Horatio Pease’s assistants were members of the Wampanoag tribe who were primarily volunteers who helped with the lighthouse’s duties and assisted him in various rescue efforts. In nearby Chilmark, the Massachusetts Humane Society Lifesavers had a life-saving station managed by Chief Simon Johnson from the local Wampanoag tribe. His crews were either fishermen or whalers who would volunteer to assist in rescue missions.

The Rescue of the City of Columbus

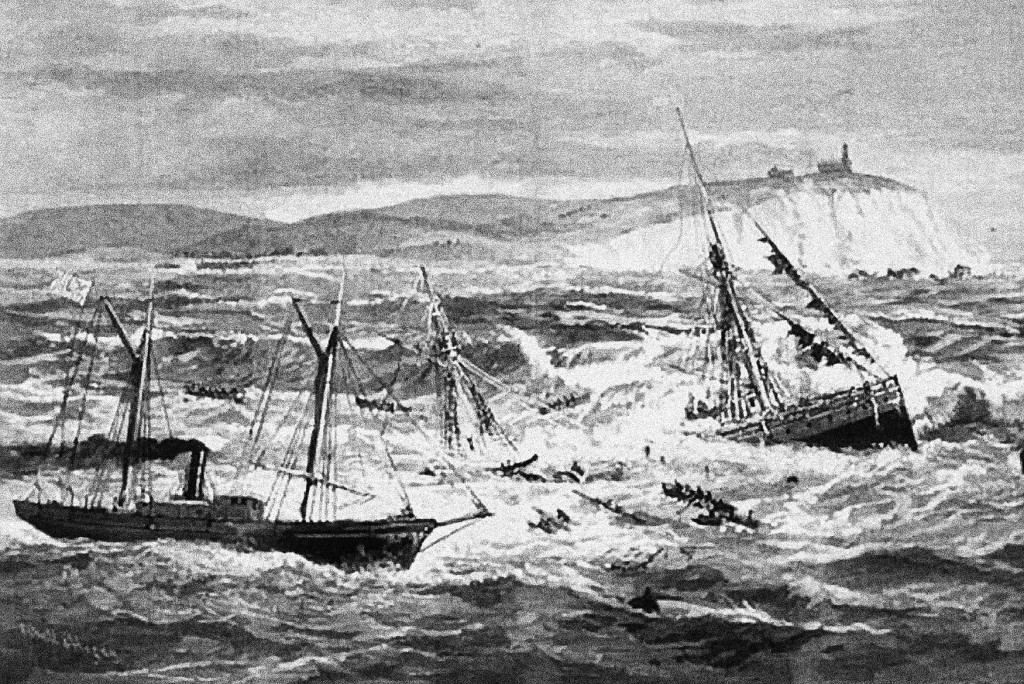

Despite the lighthouse’s powerful beams, shipwrecks often occurred in the region. One of New England’s worst maritime disasters occurred when the steamer City of Columbus, driven by gale-force winds, ran aground on Devil’s Bridge and sank at night on January 18, 1884, a bitterly cold day. The sinking drowned 103 persons on board in less than a half hour.

At around 5 a.m., the wreck was spotted over choppy surf from the shore by lighthouse Keeper Horatio N. Pease at the Gay Head Lighthouse. Pease gathered a volunteer crew of six Wampanoag Native Americans who were known as part of the Gay Head Lifesavers from the local Wampanoag tribe to assist him in the rescue. Chief Simon Johnson from the local Wampanoag tribe also headed up the Massachusetts Humane Society Gay Head Lifesaving Station in nearby Chilmark and helped to gather additional volunteers for another boat. A few Wampanoag men were sent on horseback to a telegraph station in Vineyard Haven to alert the mainland of the disaster. The one lifeboat from the wreck was also sighted near the beach by the lighthouse, and the five exhausted survivors were brought into a neighboring house and given food and dry clothes.

The first boat of Wampanoag volunteers organized by Pease was finally launched from the beach but capsized from the thunderous freezing surf. Luckily, everyone made it back to shore safely. A second attempt was made around 7:30 a.m., and reaching the stranded wreck took over an hour. After rowing over the raging waves, the rescuers were exhausted, drenched, and freezing from the bitter cold. The lifeboat crew feared approaching the steamer would cause their boat to smash into the rocks. As they neared the distressed vessel, they called those on the rigging to dive into the icy waters to be rescued. Seven reluctant passengers jumped into the sea and swam toward the lifeboat. The crew brought the craft alongside the survivors and hauled them aboard. With as much strength as they could muster, they returned over the heaving waters and biting winds toward the shore by the lighthouse and finally arrived close to the beach around 10 AM. The lifeboat was overcrowded with seven additional survivors and caught in the raging surf. It capsized a short distance from the beach, dumping everyone into the icy waters. All managed to swim to the shore and safely make it to dry land, but the boat was destroyed.

A second boat manned by the Massachusetts Humane Society Lifesavers, consisting of Wampanoag Native Americans from nearby Chilmark, rowed out to gather more survivors. The volunteer crew had recently come back from a long voyage on a successful whaling hunt. The boat was tossed around effortlessly by the enormous waves and freezing winds, making the rescue efforts exhausting. Through their tenacity in not giving up, the brave crews of Gay Head’s Humane Society managed to bring several more survivors ashore. With little time for rest, they again gathered another group of survivors determined to help at all costs, even at the risk of their own lives.

The crew of the Revenue Cutter Dexter, which happened to be in the region, heard the distress signal and aided in rescue efforts. Immediately, a boat was launched, and Lieutenant John Rhodes was in charge of five volunteers. The pounding waves carried the boat up and down as it took some time to reach the ill-fated steamer. As the lifeboat made for the wreck, it became apparent that it would be impossible to bring the craft directly alongside the masts and rigging where the remaining survivors were clinging for their lives. Upon reaching the wreck, the heavy seas were still breaking over the vessel, surrounded by debris and bodies, making the task even more difficult than expected. Rhodes yelled for the men clinging to the masts to jump into the water. One by one, seven more men jumped into the waves as Rhodes and his crew managed to get close enough to haul each onto the boat when they rose to the surface. The staff on the crowded lifeboat now returned to the Dexter, where one of the survivors died shortly afterward on deck from exposure. Exhausted and freezing from the biting winds and spray, Rhodes and his crew made another trip out to the wreck over the mountainous waves and retrieved one other reluctant survivor back to the Dexter.

As Rhodes and his crew finally had a chance to rest, Lieutenant Charles Kennedy of the Dexter, with a party of four volunteers, was lowered into the churning waters and made his way over to the wreck. The debris was still everywhere, and again the craft could not get too close to the ship, as it would certainly have been smashed against the vessel. Kennedy managed to talk four more exhausted survivors into jumping into the icy waters. As they reluctantly jumped one by one, Kennedy and his crew managed to quickly maneuver the boat to grab the struggling men into the safety of their boat. While they then made their way over the waves to the Dexter, the second lifeboat containing the 6-man crew of Wampanoag Native Americans managed to retrieve a few more survivors and transported them onto the Dexter. Again, with little time for rest, the Gay Head lifesavers started heading back towards the wreck, exhausted and freezing in the gale-force winds but determined to help recover at all costs. Rhodes went out twice and retrieved a couple more survivors, as others had perished upon reaching the Dexter.

On one attempt, as Rhodes and his crew neared the wreck, the crew of Native Americans from Gay Head were still in the area searching for any survivors. Rhodes and his assistant Roth tried to bring their boat along the wreck, but the attempts proved unsuccessful as the waves and debris prevented their efforts. Rhodes saw the Gay Head lifeboat crew and called for their help. They maneuvered their smaller craft alongside him in the churning seas, and he jumped into their lifeboat to get closer to the wreck. He tied a rope around his waist, and the brave crew were able to bring their boat within 30 feet of the wreck. Rhodes then jumped into the icy seas and started swimming towards the wreck. He nearly reached his destination over the rising waves when a large piece of timber struck him on the leg, and he began to sink. The Wampanoag crew quickly pulled him back onto the boat and found that the wood had created quite a bloody gash on his leg, which needed to be treated. All on the ship were exhausted and in danger of freezing to death from exposure. They gathered all their strength to row back to the Dexter through the stinging winds. One final attempt was made for two still clinging to the rigging, but they perished before reaching the Dexter.

Revenue Cutter Dexter on the left. City of Columbus wreck on the right. Illustration courtesy of Quest Marine Services.

By 4 p.m. that afternoon, Captain Gabrielson of the Dexter decided no more survivors were left on the wreck and pulled up anchor. He transported 21 survivors, with four who had died from exposure, and headed towards New Bedford’s port. Back at Gay Head Lighthouse on Martha’s Vineyard, the local Wampanoag families opened their homes. They provided those survivors from the one lifeboat and those brought ashore by the Native American Lifesavers assistance with food, clothing, and medical treatment to nurse them to health. The bodies and possessions of those who had perished and washed ashore were brought to the Gay Head Community Baptist Church to be claimed.

Despite the frigid weather and terrible gale-force winds, both the Wampanoag men and the crews on the Dexter repeatedly went into the icy waters out to the wreck of the City of Columbus, risking their own lives to ensure all survivors were rescued. The Native American volunteers of the Gay Head lifesaving crews were involved in the rescue of 21 of the 29 survivors from the wreck. They managed to row out multiple times through the raging surf from the beach to the wreck and bring some survivors back to the shore for help until the revenue cutter, Dexter, arrived. Determined to help at any cost, they went out and assisted in transporting survivors from the wreck to the Dexter.

The Wampanoag Native Americans who made up the Gay Head Light and Massachusetts Humane Society Lifesavers and the crew of the Dexter were honored for their “brave and humane conduct.” They were written about locally and nationally as heroes. The Massachusetts Humane Society awarded each Wampanoag Native American volunteer rare silver or bronze medals for their heroic efforts.

This coordination of the branches of the Lighthouse Service, Life Saving Service, and also the Revenue Cutter Service became one of the first successful coordinated attempts, which led to many more successful future rescues in other regions. These three rescue branches evolved into our current Coast Guard in 1915.

Gay Head’s First Native American Keeper

Gay Head Lighthouse also had the first Native American Keeper, Charles Vanderhoop, an Aquinnah Wampanoag Indian born in 1882. He became one of the lighthouse’s most popular keepers known for his openness in allowing many tourists and locals to enjoy the view from the top of Gay Head Lighthouse tower during his service from 1910 through 1933. It is believed he entertained over 300,000 guests during his tenure, including President Calvin Coolidge. He and his brother Bert also owned a restaurant near the lighthouse, initially owned by their parents.

Exploring the Western Side of Martha’s Vineyard

The area is beautifully quiet on the western shoreline of Martha’s Vineyard, where people come to relax and enjoy walking along Moshup Beach below the cliffs for spirituality and to enjoy the views. At times, nudists for connectivity frequent it. Aquinnah and Chilmark are for those who desire to relax and escape the busy ports. When you visit Martha’s Vineyard, explore this quiet area and think of the historical significance of the Wampanoag Native Americans to the success of Gay Head Lighthouse.

Check out my photos of Gay Head (Aquinnah) Lighthouse.

Enjoy,

Allan Wood

Books to Explore

New England’s Haunted Lighthouses:

Ghostly Legends and Maritime Mysteries

Discover the mysteries of the haunted lighthouses of New England! Uncover ghostly tales of lingering keepers, victims of misfortune or local shipwrecks, lost souls, ghost ships, and more. Many of these accounts begin with actual historical events that later lead to unexplained incidents.

Immerse yourself in the tales associated with these iconic beacons!

The Rise and Demise of the Largest Sailing Ships:

Stories of the Six and Seven-Masted Coal Schooners of New England.

In the early 1900s, New England shipbuilders constructed the world’s largest sailing ships amid social and political reforms. These giants were the ten original six-masted coal schooners and one colossal seven-masted vessel, built to carry massive quantities of coal and building supplies and measured longer than a football field! This self-published book, balanced with plenty of color and vintage images, showcases the historical accounts that followed these mighty ships.

Available also from bookstores in paperback, hardcover, and as an eBook for all devices.

Book – Lighthouses and Coastal Attractions in Southern New England: Connecticut, Rhode Island, Massachusetts

Lighthouses and Coastal Attractions of Southern New England:

Connecticut, Rhode Island, and Massachusetts.

This 300-page book provides memorable human interest stories from each of the 92 lighthouses, including the story of survivors rescued from the City of Columbus in Massachusetts. You can explore plenty of indoor and outdoor coastal attractions, including whale-watching excursions, lighthouse tours, windjammer sailing tours, parks, museums, and even lighthouses where you can stay overnight. You’ll also find plenty of stories of hauntings around lighthouses.

Lighthouses and Coastal Attractions of Northern New England:

New Hampshire, Maine, and Vermont.

This 300-page book provides memorable human interest stories from each of the 76 lighthouses. It also describes and provides contact info for plenty of indoor and outdoor coastal attractions and tours. These include whale watching, lighthouse tours, unique parks, museums, and lighthouses where you can stay overnight. There are also stories of haunted lighthouses in these regions.

New England Lighthouses:

Famous Shipwrecks, Rescues & Other Tales

This book contains over 40 stories, including the rescue of the City of Columbus survivors off Martha’s Vineyard Island in Massachusetts. It is also image-rich, with vintage images provided by the Coast Guard and various organizations and paintings by six famous Coast Guard artists.

You can purchase this book and the lighthouse tourism books from the publisher Schiffer Books or in many fine bookstores such as Barnes and Noble.

Copyright © Allan Wood Photography, do not reproduce without permission. All rights reserved.

Join, Learn, and Support The American Lighthouse Foundation