Keeper Horace Arnold and His Son Battle Ice Floes

Smashing Into Conimicut Shoal Light, in Rhode Island

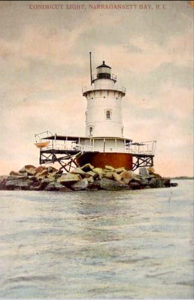

In 1868, the granite tower Conimicut Shoal Lighthouse was built at the entrance to the Providence River, which empties into Narragansett Bay, about a mile from the nearest shore. Early keepers were not provided with living quarters at Conimicut Lighthouse. They had to make daily mile-long trips in a rowboat that was sometimes quite dangerous to nearby Nayatt Point Lighthouse onshore for overnight stays. In the wintertime, as the river empties into the salt water of Narragansett Bay, ice floes, looking like thick frozen islands, would form from the frozen seawater. They would be carried downriver and collide into anything in their path with the surge of tides.

On February 27, 1874, Horace W. Arnold was appointed the new lighthouse keeper. He was an eighth-generation descendant of Benedict Arnold, the famous Revolutionary War traitor, but Horace himself was one of honesty and integrity. He was a Civil War veteran from Rhode Island and had served two years as an assistant keeper at Beavertail Light. A few months later, in 1874, a five-room keeper’s dwelling was built on the pier by the lighthouse, a welcome addition for his family. Unfortunately, as in many of these dwellings, they were not made strong enough to resist the constant onslaught of New England storms or ice floes.

On March 3, 1875, temperatures had plummeted around the region, and a fierce gale storm was coming down from the northeast of Canada. Keeper Arnold remained at the lighthouse with his nine-year-old son, Earnest, while his wife and the other children had gone ashore to visit overnight with a family friend. Arnold and his son were fast asleep in the post-midnight hours of March 4 as a large field of ice floes started down the Providence River from Bullock’s Cove. The gale-force winds helped to increase the speed of these frozen chunks of ice as they continued down towards the lighthouse on Narragansett Bay.

At about 5:30 that morning, Horace Arnold and his son were awakened by the sound and vibrations of the ice floes crashing into the wooden structure. They were in their night clothes and sleeping on the upper floor. The foundation proved too weak as the ice rammed into it, causing one of the walls to collapse. Soon, the rest of the structure followed and collapsed towards the river as it was moved a short distance away from the tower by the gusting winds. The tenacious keeper, clinging to the debris, kept his son close to him and found a blanket to wrap around the shivering and frightened boy. Both struggled amid the debris in the freezing waters as gale-force winds and stinging snow raged around them.

Realizing the need to attract attention to contact those on the shore of their dangerous predicament, Keeper Arnold grabbed a water-soaked mattress and tied it to the most robust remaining section of the collapsed building. He secured Earnest to the mattress as he made his way up the lighthouse tower and set up a distress signal by ringing the bell for anyone within listening range.

Captain Nat Sutton of the tugboat Reliance out of Providence heard the bell ringing from the tower and, unable to reach the shoal and perform the rescue by himself, found the schooner Oliver Jameson about a mile away to help with the rescue. He grabbed the schooner’s crew with their lifeboat and headed toward the lighthouse as the gale-force winds raged on. Seeing the tugboat approaching, the keeper crawled down from the tower and stayed with his son on the mattress. The poor child was exhausted and frozen as he had been waiting on it for about three hours and may not have lasted much longer with only a blanket and scanty night clothes in freezing temperatures and winds. Captain Sutton later wrote that the keeper appeared on an ice flow from a distance, as if “sitting like a man on a magic carpet.”

With the winds beginning to subside, the crew from the schooner could maneuver their small rescue boat to reach the two survivors and bring the keeper and his son onto the Reliance. Both father and son were in rough shape from frostbite, and the keeper was brought to Nayatt Point Light across the river to notify his agonized family and friends of the rescue. The boy, partially clothed, was brought by the tug to Newport Harbor, where friends and family met him to provide warm clothing, including socks and shoes he was missing. He was brought to a local hospital and cared for frostbite. He stayed with a family relative briefly while his family worked on getting Nyatt Point Light set up for the family.

The tug Reliance went back to help secure the remains of the dwelling and to try to save any furnishings, but little was found. Both father and son were severely frostbitten, with Keeper Arnold’s condition involving months of hospitalization before he could return to duty at the lighthouse. The lighthouse survived the ice floes, but the keeper’s house was destroyed, so the family stayed at the nearby inactive Nayatt Point Light until the quarters were rebuilt.

A few months later, on August 2, 1875, a tragedy came upon the Arnold family. Keeper Arnold, his son Earnest, and the younger seven-year-old brother were at the lighthouse. The two boys were near the lighthouse tower when the youngest son slipped off the platform and fell seventeen feet to the granite stones surrounding the lighthouse’s foundation. Arnold rang the bell to send out a distress signal as the injured boy was bleeding from his head. He was brought to Nayatt Point as Dr. Bullock of Warren and Dr. Miller of Providence were called to treat him. Both doctors determined the poor child had a fractured skull and a broken arm. They did everything they could to help the boy, but he died two days later.

Conimicut Lighthouse was Rebuilt in 1883 with a Platform and Keeper’s Quarters Inside (postcard circa 1907)

The Arnold family had lost most of their possessions from the ice floes incident and ended up living at Nayatt Point Lighthouse, which, fortunately, the government had not yet sold as was initially planned. Four years later, in 1879, Keeper Arnold was finally awarded $319 as compensation for his possessions lost in the incident.

The granite tower was replaced with an iron tower in 1883. The new tower was built with rooms for the keeper and his family. Arnold moved from the Nayatt Point keeper’s dwelling to the new lighthouse in 1884. Horace Arnold was credited with saving the lives of five people during his 12 years at Conimicut Shoal Light. He left in 1886 to become keeper of North Conanicut Island Lighthouse in Rhode Island, a short distance away, where he would stay for the remaining 28 years of his career.

Books to Explore

New England’s Haunted Lighthouses:

Ghostly Legends and Maritime Mysteries

Discover the mysteries of the haunted lighthouses of New England! Uncover ghostly tales of lingering keepers, victims of misfortune or local shipwrecks, lost souls, ghost ships, and more. Many of these accounts begin with actual historical events that later lead to unexplained incidents.

There are hauntings at Conimicut Shoal Light of a keeper’s wife who was involved with a murder-suicide. Immerse yourself in the tales associated with these iconic beacons!

The Rise and Demise of the Largest Sailing Ships:

Stories of the Six and Seven-Masted Coal Schooners of New England.

In the early 1900s, New England shipbuilders constructed the world’s largest sailing ships amid social and political reforms. These giants were the ten original six-masted coal schooners and one colossal seven-masted vessel, built to carry massive quantities of coal and building supplies and measured longer than a football field! This self-published book, balanced with plenty of color and vintage images, showcases the historical accounts that followed these mighty ships.

Available also from bookstores in paperback, hardcover, and as an eBook for all devices.

Book – Lighthouses and Coastal Attractions in Southern New England: Connecticut, Rhode Island, Massachusetts

Lighthouses and Coastal Attractions of Southern New England:

Connecticut, Rhode Island, and Massachusetts.

This 300-page book provides memorable human interest stories from each of the 92 lighthouses, including Conimicut Lighthouse in Rhode Island. You can explore plenty of indoor and outdoor coastal attractions, including whale-watching excursions, lighthouse tours, windjammer sailing tours, parks, museums, and even lighthouses where you can stay overnight. You’ll also find plenty of stories of hauntings around lighthouses.

Lighthouses and Coastal Attractions of Northern New England:

New Hampshire, Maine, and Vermont.

This 300-page book provides memorable human interest stories from each of the 76 lighthouses. It also describes and provides contact info for plenty of indoor and outdoor coastal attractions and tours. These include whale watching, lighthouse tours, unique parks, museums, and lighthouses where you can stay overnight. There are also stories of haunted lighthouses in these regions.

Copyright © Allan Wood Photography; do not reproduce without permission. All rights reserved.

Join, Learn, and Support The American Lighthouse Foundation