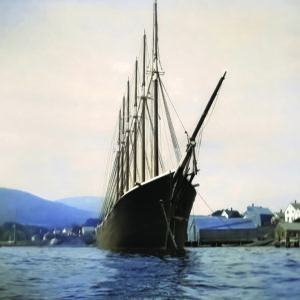

Six-Masted Schooner George W. Wells Under Full Sail

Image Camden Public Library (1900)

The First Six-Masted Sailing Ship, the George W. Wells, Built in Camden, Maine

Early merchant or cargo ships used the square-rigged sail design, where wooden horizontal spars carried most of the primary sails perpendicular to the masts. They were slower than schooner sailing ships and needed large crews of at least 30 men to climb up in the rigging to raise and lower the sails and maintain the ship. Schooners proved to be the favored design for hauling coal over the previous “square riggers.” These coal schooners, or colliers as they were called, were explicitly designed as bulk cargo ships to carry large quantities of coal in one trip. Their unique triangular and angular four-sided sails gave these vessels unlimited range as they relied only on sail propulsion, although they depended on weather conditions. They were faster in deep open waters and were relatively inexpensive to operate, as they could be handled by smaller crews, saving ship owners money on hiring sailors.

Four and five-masted schooners could carry 3,000 to 4,400 tons of cargo. However, with the new economy booming in the late 1890s, the race was on among shipbuilders to effectively design larger six-masted schooners to transport even more coal and construction materials to increase profits, with capacities of delivering between 5,000-6,000 tons. The creation of these giants became a reality between 1900-1909. The first of these largest vessels was the George W. Wells, constructed in 1900 at the Holly M. Bean Shipyard in Camden, Maine, under the direction of Captain John G. Crowley, who was also the primary investor. The Crowley family had started the Coastwise Transportation Company, in which they were building a fleet of smaller and heavier steel-hulled ships out of the Fore River Ship and Engine Company at the shipyard in Quincy, Massachusetts. He had previously engineered and built the largest five-masted wooden schooner, the John B. Prescott, at the Bean Shipyard in Camden, Maine.

The ship, named after George Washington Wells, one of the owners of the American Optical Company in Southbridge, Massachusetts, was launched in front of over 10,000 excited people on August 4, 1900. His daughter, Mary Wells, scattered roses and released a flock of doves as the schooner slid into the waters. She sailed around the harbor by Curtis Island Light as tests and measurements were made and returned without any issues. In her original launching, temporary masts were used instead of permanent masts, which weren’t ready for installation. The purpose was to beat the scheduled launching of the Eleanor A. Percy, which the owners from the Percy & Small Shipyard in Bath, Maine, had initially planned to become the “first” six-masted schooner.

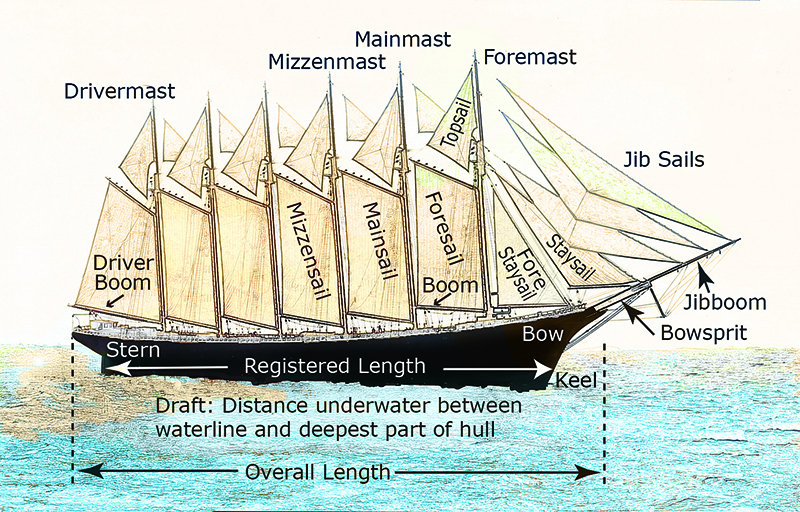

The George W. Wells measured 303 feet along her registered keel length at the waterline, 48 feet wide, and 23 feet deep to hold over 5,000 tons of cargo. When fully loaded, her draft, or the underwater distance between the waterline and the deepest part of the hull, would be 24 feet. Her overall length across the deck top from the tip of the bow to the stern, not including the bowsprit or booms, was 345 feet. As was customary for sailing vessels, she also attached to her bowsprit a giant jibboom measuring 75 feet to add extra jib sails to help handle the ship when turning through the wind with the bow. From the tip of her front jibboom to the end of her rear driver boom extending over the deck, she measured an impressive 425 feet.

The ship used over a million feet of hard pine, with hardwoods, primarily white oak and others like ash, sycamore, and cherry, to frame the deck and cabins. The 550 tons of solid white oak came from the famous White House plantation. One of the original owners of the plantation was Confederate General Robert E. Lee, who commanded the Southern Army during the Civil War. Other high-quality materials were also used in its construction, with the ship costing around $120,000 (today would be 4.2 million dollars) to complete. She had unique amenities like a wheelhouse, rarely incorporated in coastal cargo vessels, with cabins and staterooms that included hot and cold baths, electric bells, and a telephone line for the captain or his officers to communicate with the galley and engine room.

Construction of Six-Master George W. Wells in Camden, Maine

Original B&W Image Courtesy Camden Public Library

After the initial fanfare with her launching, the George W. Wells was put back into dry dock for a few weeks to assemble the permanent masts and for final inspection before her maiden voyage. Each of the vessel’s final six masts, measuring over 119 feet tall, is made of Oregon pine and has a width of about 30 inches at the base. Topmasts were attached and would measure another 58 feet in length. The six masts were named from front to back as foremast, mainmast, mizzenmast, spankermast, jiggermast, and drivermast.

The George W. Wells became the largest wooden merchant ship afloat. Captain Arthur L. Crowley, the brother of owner Captain John G. Crowley, would command the schooner. The new commander also spent much time at sea as a young lad along with his brother. On September 15, 1900, the six-master was towed out to sea past Monhegan Island Lighthouse by the tug Bismarck, bound for the Delaware Breakwater. On her maiden voyage, Captain Crowley chartered to pick up her first load of coal from Baltimore, Maryland, for delivery to Boston, Massachusetts. The giant collier arrived in Baltimore on October 4, 1900. With her five special hatches, she could load 200 tons of coal every five minutes, filling her hull with 5,000 tons of cargo in ten hours, breaking all records. A nasty gale storm approached as the George W. Wells headed out of the Chesapeake Bay, causing the great ship to retreat to Newport News in Virginia to shelter until the weather calmed.

By early Thursday, October 18, 1900, the keeper of Nobska Lighthouse at Woods Hole on the mainland had sighted the George W. Wells in Vineyard Sound. The schooner sailed past Boston Harbor Lighthouse early that evening. It would be the largest cargo of coal ever brought to Boston Harbor on a single sailing ship, proving that she could be very profitable. As soon as she unloaded, the captain chartered another load of coal from Philadelphia for delivery to Havana, Cuba.

In New England, fierce storms would occur frequently and with little notice. As the George W. Wells started heading out towards Cape Cod on route to Philadelphia, a violent gale storm engulfed the region, forcing her and a fleet of other boats to anchor at Provincetown Harbor, located at the tip of Cape Cod, until the storm passed. The intense wind gusts continued for days until October 31, 1900, when the storm finally went out to sea. The tug Tormentor towed the six-master out to the open waters as she continued her journey south.

After acquiring coal in Philadelphia, she proved to be a fast ship, as she journeyed to Havana in seven days, arriving at the port on November 22, 1900. Many other vessels could make the same trip in 8-12 days. The schooner unloaded her cargo in Havana Harbor, then returned to port at Brunswick, Georgia, to pick up a record load of 50,000 railroad ties for delivery to New York for the continued construction of the Erie Railroad. Shipments of railroad ties were at most 12,000 ties, proving how efficient the vessel would be. When the George W. Wells arrived at the port of New York three days later, she created quite a sensation for news reporters and crowds alike who came to view the giant collier up close.

By April of 1901, the first six-masted schooner had gained the respect of sailing professionals, proving that not only was she profitable with her ability to carry up to 5,000 tons of cargo, but that she was also one of the fastest sailing ships, even beating many of her steamship competitors. With the wooden giant capturing the attention of the press with its success, many reporters started pushing the idea of building an even larger seven-masted schooner to Crowley, who began working on the possibility of constructing such a vessel.

Books to Explore

New England’s Haunted Lighthouses:

Ghostly Legends and Maritime Mysteries

Discover the mysteries of the haunted lighthouses of New England! Uncover ghostly tales of lingering keepers, victims of misfortune or local shipwrecks, lost souls, ghost ships, and more. Many of these accounts begin with actual historical events that later lead to unexplained incidents.

Immerse yourself in the tales associated with these iconic beacons!

The Rise and Demise of the Largest Sailing Ships:

Stories of the Six and Seven-Masted Coal Schooners of New England.

In the early 1900s, New England shipbuilders constructed the world’s largest sailing ships amid social and political reforms. These giants were the ten original six-masted coal schooners and one colossal seven-masted vessel, built to carry massive quantities of coal and building supplies and measured longer than a football field! This book, balanced with plenty of color and vintage images, showcases the historical accounts that followed these mighty ships, like the construction of the George W. Wells in Bath, Maine, and its maiden voyage.

Available also from bookstores in paperback, hardcover, and as an eBook for all devices.

Book – Lighthouses and Coastal Attractions in Southern New England: Connecticut, Rhode Island, Massachusetts

Lighthouses and Coastal Attractions of Southern New England:

Connecticut, Rhode Island, and Massachusetts

This book provides memorable human interest stories from each of the 92 lighthouses. You can explore plenty of indoor and outdoor coastal attractions, including whale-watching excursions, lighthouse tours, windjammer sailing tours, parks, museums, and even lighthouses where you can stay overnight. You’ll also find plenty of stories of hauntings around lighthouses, like the story of “Ernie” above.

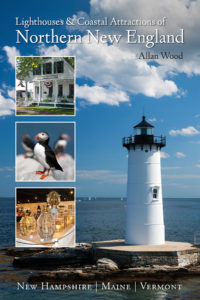

Lighthouses and Coastal Attractions of Northern New England:

New Hampshire, Maine, and Vermont

This book provides memorable human interest stories from each of the 76 lighthouses. It also describes and provides contact info for plenty of indoor and outdoor coastal attractions and tours. These include whale watching, lighthouse tours, unique parks, museums, and lighthouses where you can stay overnight. There are also stories of haunted lighthouses in these regions.

Copyright © Allan Wood Photography; do not reproduce without permission. All rights reserved.

Join, Learn, and Support The American Lighthouse Foundation