Early Voyages of the Largest and Only Seven-Masted Sailing Ship, the Thomas W. Lawson

Launching the Largest Sailing Ship Ever Built

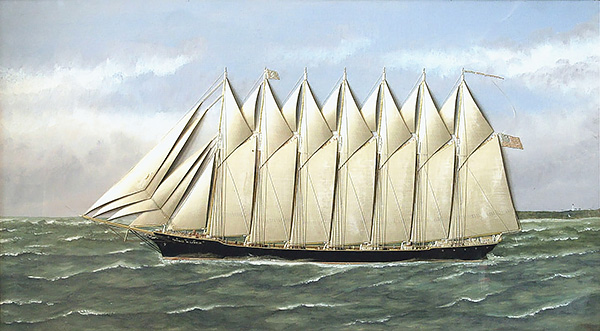

On July 10, 1902, the Thomas W. Lawson was launched from the Fore River Ship and Engine Company shipyard in Quincy, Massachusetts. This shipyard was renowned for constructing steel-hulled vessels. This massive coal schooner was the first and only seven-masted ship ever built, boasting an impressive capacity to carry up to 11,000 tons of coal, although its hull depth, or draft, was 36 1/2 feet below the waterline. However, this made it unlikely that she could load to capacity at any port without costly dredging or land removal before accommodating the ship, which was not feasible. In most cases, her full load would not exceed 8,200 tons, allowing her to safely discharge with her deep draft of nearly 27 feet at specific ports. The gigantic ship measured 403 feet across the deck, 368 feet at the waterline, had a beam of 50 feet, and a depth of 36 feet, making her the largest ship afloat in 1902. Her bowsprit, made of steel, measured 85 feet in length. From the tip of her pusher boom at the rear to the tip of her bowsprit at the front, she measured 475 feet. The seven lower masts stood 155 feet tall, carrying 43,000 square feet of canvas for 25 sails. The lower masts were made of steel and were hollow inside, while the topmasts, each measuring 58 feet long, were constructed from Oregon pine. This resulted in a total height of 189 feet after accounting for the connections of each of her masts. The giant ship had six engines along her deck to raise and lower the sails and perform other heavy tasks, including moving the two enormous anchors weighing 10,000 pounds each.

The christening was made by Helen Watson, daughter of Thomas A. Watson of East Braintree and President of the Fore River Ship and Engine Company. He was the famous assistant of Alexander Graham Bell, the inventor of the telephone. He had initially started the company in East Braintree as The Fore River Engine Company in 1886. Soon afterward, the company and the shipyard were moved to Quincy, becoming The Fore River Ship & Engine Company.

Thomas W Lawson; by Thomas Willis, Painting with oils and silk (1907).

Courtesy New York Public Library, via Picryl.

The ship was named after the Boston copper baron, millionaire stockbroker, and yachtsman Thomas W. Lawson. Bowdoin B. Crowninshield, a naval architect known for his racing yachts for Captain John G. Crowley of the Coastwise Transportation Company in Boston, Massachusetts, designed it. She was to be captained by Captain Arthur L. Crowley, John’s brother, who had previously commanded the George W. Wells, the first six-masted schooner built in 1900. A crew of 16 men would manage this massive vessel. After the ceremony concluded in front of 20,000 spectators, she was returned to dry dock in the shipyard for final checks of equipment and measurements, along with setting up the sails and rigging.

In September of 1902, the Thomas W. Lawson was ready to be tested outside Boston Harbor. However, due to its immense size and height, the Quincy Point Bridge, a draw bridge over the Fore River, had to be cut away to accommodate the giant schooner. The original bridge was an old wooden structure built in 1812 and was planned to be torn down anyway. The new structure would be constructed of granite and steel at 100 feet wide, to accommodate the larger vessels of the future to pass through. When the bridge was removed on September 9, 1902, the Thomas W. Lawson was towed down the river by two tugboats to help maneuver the great vessel. She was commanded by Pilot Captain Cleverly to make her way down the winding river through the demolished old draw bridge and out to the harbor, where Captain Arthur Crowley would take over the duties of commanding the vessel. Crowley married Mertie Blake the night before, so she accompanied the captain on the voyage to the harbor.

Challenges on Her Maiden Voyage and Second Charter

Captain Crowley struggled to find a crew for the ship’s first voyage to pick up a load of coal from Philadelphia. He attempted to recruit only 10 men for the first voyage, but the Atlantic Coast Seamen’s Union, to which most men belonged, believed he needed a crew of at least 12. Crowley then sought to secure Portuguese seamen from Boston, but was again unsuccessful, as they had all joined the union. After much deliberation, the captain conceded and hired 15 crew members from the union to start immediately.

Thomas W. Lawson After Launch

Original B&W newspaper image (circa 1902)

© Allan Wood Photography, all rights reserved.

With all tests completed and the crew ready to set sail, on September 12, 1902, at 9 a.m., the Thomas W. Lawson began her maiden voyage out of Boston Harbor. Three tugs towed her out past Minot’s Ledge Lighthouse. The winds blew from west-southwest to southeast, causing the great vessel to sail into the wind, a maneuver known as beating to windward, as she slowly but steadily headed south. Captain Crowley’s newly married wife accompanied him on this first voyage as a honeymoon for both. The steel schooner arrived safely in Philadelphia a couple of weeks later with her first cargo of coal to be delivered to Boston.

It took several weeks to bring her into port and load her with a cargo of 7,734 tons of coal. As the giant schooner left Philadelphia for Boston on October 23, 1902, her deep draft caused her to run aground in the mud about 20 miles south of the city. The area, known as Cherry Island Flats in the Delaware River, consisted of a cluster of muddy shoals, complicating navigation for larger ships. Tugs were dispatched to assist in moving her, and as the tides came in, they successfully floated her free. However, she did not travel far before grounding again in the mud, and once more, tugs were called in during the next high tide. Many mariners began to doubt her efficiency, as her loaded draft below the waterline, carrying only a portion of her capacity, was extreme at nearly 27 feet and would pose challenges in many ports. Others believed that if the ship had struck a rocky shoal, her fate might have been different, expressing concerns that the builders and engineers involved in her construction had pushed the limits of a steel vessel. She arrived in Vineyard Sound on October 27, 1902, and anchored overnight outside Vineyard Haven on Martha’s Vineyard to wait for daylight. Ultimately, she came into Boston Harbor with the largest cargo of coal ever carried by a single vessel.

Although the Thomas W. Lawson was built to hold over 11,000 tons of coal, this resulted in an extremely low draft near capacity, making it nearly impossible to load or unload that much cargo at any port, and dredging to accommodate her would be too expensive. It was calculated that if she were ever loaded to full capacity, her draft would be an unimaginable 35 to 37 feet. In fact, she could load up to 8,000 tons to safely unload in many major ports, but even that amount could cause issues, as she experienced on her maiden voyage.

On her second charter for coal, the captain decided to try to load nearly 8,000 tons from Baltimore. Unfortunately, when the largest ship left Baltimore on November 22, she again touched bottom as she was heading out but was able to continue safely. The winds were fair, and she unloaded in Boston Harbor without incident, making it the largest amount of coal unloaded by one sailing vessel.

After the first few voyages, the giant schooner became the target of criticism from marine writers and some seamen, as she was difficult to maneuver and sluggish. Those employed on the ship compared the experience of handling such a colossal vessel to managing a giant “bathtub” or a “beached whale.” The Thomas W. Lawson proved problematic in the ports where she was intended to operate due to the amount of water she displaced. With her extreme length, she also tended to “twist” to the sides and required a strong wind to maintain her course.

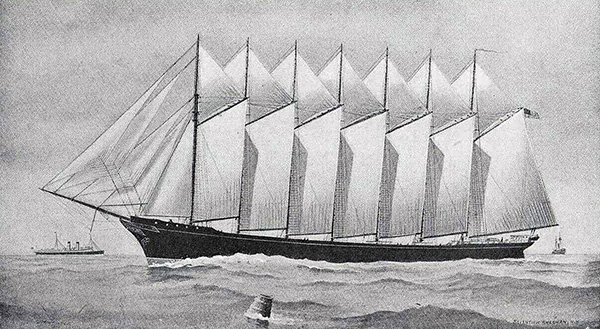

Illustration of Thomas W. Lawson

Washington Library, from Scientific American, via Picryl (circa 1913)

Problems on the Next Voyage with an Accidental Tragedy

Captain Crowley indicated his desire to load more cargo from the deeper channel of Newport News near Norfolk, Virginia. He aimed to carry a load closer to 9,000 pounds but was still short of the collier’s full capacity. He chartered a third voyage from Newport News to Boston. On this third voyage, he loaded 8,010 tons of coal, which remained the largest amount ever transported on a single sailing vessel. The schooner experienced no issues leaving the deep channel of Newport News and proceeded up the coast, carrying a deep draft of nearly 27 feet below the waterline.

On February 6, 1903, the Thomas W. Lawson entered Vineyard Sound late that night. Strong winds were blowing in the region, creating heaving waves from a storm at sea. The massive vessel suddenly ran aground around 5:30 a.m. on the east end of Middle Ground Shoal, situated between West Chop Lighthouse on Martha’s Vineyard and Woods Hole on the mainland. Mountainous waves were still crashing as the Boston Towboat Company’s wrecking tug, the Underwriter, went to assist the ship and arrived later that morning.

A strong current flowed through the sound as the tug attempted to move the schooner that morning but was unsuccessful. The current carried the Underwriter away from the schooner, causing it to ground nearby on a section of the same shoal. By noon, both ships remained stuck on the shoal, although neither vessel faced any danger.

As the Underwriter attempted to pull the Thomas W. Lawson off the shoal, 40-year-old local worker Mate Bevens was struck hard on the head by a component of the tug’s steering gear. The blow was so severe that it fractured the base of his skull. A short time later, the tug Storm King was passing by, towing a barge from New York, and saw the Underwriter’s distress signal. She anchored her tow and sent out a boat to rescue the injured Bevens, bringing him to a nearby marine hospital. Upon examination, it was determined that the injury was so severe it was believed to be fatal, and he passed away the next day.

After the Storm King dropped off the injured seaman, the tug returned to attempt to float the grounded tug Underwriter. The seas were beginning to subside as high tide came in, allowing the Underwriter to float off the shoal later that afternoon without assistance. The tide had risen higher than usual, enabling the stronger current to carry the undamaged Thomas W. Lawson off the shoal as well. The Storm King picked up the barge it had previously anchored to assist and continued on to its destination.

A severe southeast gale struck the Cape Cod region as the Thomas W. Lawson headed out and rounded Nantucket Sound. It forced the schooner and many other vessels to anchor outside Chatham near Handkerchief Shoal, away from the rough seas. After a couple of days waiting out the storm, she set sail around Cape Cod toward Boston Harbor. With her deep draft due to the heavy load, it took four tugboats to move her to the South Boston pier while the tide was coming in to unload her cargo.

The giant ship proved very profitable for its owners, but its lifespan was short. In December 1907, she sank in a storm along the Isles of Scilly off the coast of England.

Books to Explore

New England’s Haunted Lighthouses:

Ghostly Legends and Maritime Mysteries

Discover the mysteries of the haunted lighthouses of New England! Uncover ghostly tales of lingering keepers, victims of misfortune or local shipwrecks, lost souls, ghost ships, and more. Many of these accounts begin with actual historical events that later lead to unexplained incidents.

Immerse yourself in the tales associated with these iconic beacons!

The Rise and Demise of the Largest Sailing Ships:

Stories of the Six and Seven-Masted Coal Schooners of New England.

In the early 1900s, New England shipbuilders constructed the world’s largest sailing ships amid social and political reforms. These giants were the ten original six-masted coal schooners and one colossal seven-masted vessel, built to carry massive quantities of coal and building supplies and measured longer than a football field! This self-published book, balanced with plenty of color and vintage images, showcases the historical accounts that followed these mighty ships.

You’ll find more details of the Thomas W. Lawson‘s initial voyages and many more stories, including its final voyage and the infamous rescue of a few survivors when the ship went down off the coast of the Isles of Scilly in England.

Available also from bookstores in paperback, hardcover, and as an eBook for all devices.

Book – Lighthouses and Coastal Attractions in Southern New England: Connecticut, Rhode Island, Massachusetts

Lighthouses and Coastal Attractions of Southern New England:

Connecticut, Rhode Island, and Massachusetts.

This 300-page book provides memorable human interest stories from each of the 92 lighthouses, like the story of the keeper’s granddaughter saving Elm City at Stratford Point Light. You can explore plenty of indoor and outdoor coastal attractions, including whale-watching excursions, lighthouse tours, windjammer sailing tours, parks, museums, and even lighthouses where you can stay overnight. You’ll also find plenty of stories of hauntings around lighthouses.

Lighthouses and Coastal Attractions of Northern New England:

New Hampshire, Maine, and Vermont.

This 300-page book provides memorable human interest stories from each of the 76 lighthouses. It also describes and provides contact info for plenty of indoor and outdoor coastal attractions and tours. These include whale watching, lighthouse tours, unique parks, museums, and lighthouses where you can stay overnight. There are also stories of haunted lighthouses in these regions.

Copyright © Allan Wood Photography; do not reproduce without permission. All rights reserved.

Join, Learn, and Support The American Lighthouse Foundation