Rescuing Mariners Using Revenue Cutters, Tugs, and Other Rescue Boats

The Revenue Marine Service used sailing vessels called revenue cutters in times of war and for law enforcement in protecting our shores when it was first created during colonial times by President George Washington. These ships were designed for speed instead of capacity and could travel into shallow water, making them ideal for patrolling the coastline. It wasn’t until the 1830s that these fast vessels proved effective for rescue purposes, mainly out in open waters, miles offshore, where lighthouse keepers or trained lifesavers at lifesaving stations could not reach stranded ships.

During the Civil War, the Revenue Marine Service became an armed maritime police force, providing security for their home ports. Those officers on board these boats were sometimes called “cuttermen.” These men boarded vessels, searched for illegal cargo, enforced federal laws, and protected commerce from enemy cruisers. Their duties involved boarding foreign and domestic ships to check for documentation and vessel safety and stemming the flow of illegal cargoes, such as enslaved people or war munitions. The Revenue Marine Service’s fleet greatly expanded during the war and changed from mostly sailing ships to primarily steam-powered vessels.

After the Civil War, smaller “cutters” were also built to patrol more closely to the coastline and were responsible for saving many lives from wrecks within harbors or offshore. Later, they became involved in rescue coordination efforts with personnel from lighthouses and lifesaving stations. Other smaller vessels built would be the tugboats, sometimes called steam tugs, as they used steam engines for propulsion. They were not fast but wide and bulky to prevent capsizing in stormy weather. These unique boats would tow and guide vessels into ports or assist in coordinated rescue efforts with the larger, sleeker revenue cutters to help survivors of wrecks offshore.

Steam Tugboat at East River Docks, NY (circa 1901). Original B&W image courtesy Library of Congress.

The Lighthouse Service, the Life Saving Service, and the Revenue Marine Service became the three branches of marine rescue service to aid those in distress. Both personnel of lighthouses and lifesaving stations were funded by and reported to the U.S. Lighthouse Service. The Revenue Marine Service, officially renamed the Revenue Cutter Service in July 1894, operated under the U.S. Department of the Treasury. Years later, in 1915, they combined to become our current Coast Guard.

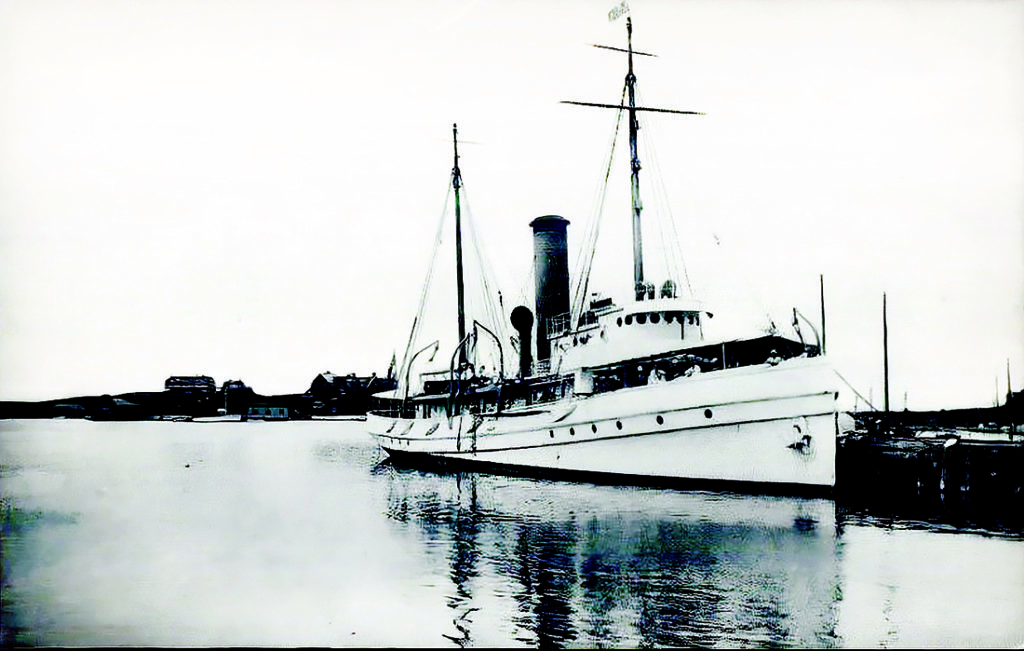

From the Civil War into the early 1900s, the design of revenue cutters as two and three-masted steam-powered vessels helped to make them independent of the weather as opposed to their earlier wooden schooner counterparts. They could use either sails or steam engines for propulsion. They were built strong, mainly of steel hulls, and at a relatively large size of around 100-150 feet in length. Their size helped move larger stranded vessels grounded on shoals and reefs or to help rescue survivors from wrecks. They would use various anchors and chains from the boat in distress or use their wrecking apparatus to hook onto the ship and try to move it carefully during high tides. Harbor or port tugs would assist the larger cutters in pulling off these boats from where they had grounded and in helping to move them to safety.

Revenue Cutter Dexter out of Woods Hole, Massachusetts (circa 1876). Image Courtesy of US Coast Guard

There were other types of boats to help stranded wrecks or aid vessels. Lighthouse tenders were ships specifically designed to maintain, support, or tend to lighthouses, mobile lightships, and other ships in providing supplies, fuel, mail, and transportation when needed. Ships called “lighters” were flat-bottomed barges used to transfer cargo, equipment, and stranded passengers to and from those ships in distress. Skilled workers who operated these boats, called “lightermen,” helped to remove some of the cargo or equipment from a grounded vessel to lighten it. With some of the weight removed, the ship could float off the point where it had grounded with the help of the revenue cutter and local tugboats. Wrecking tugs were also built to provide equipment and assistance to stranded vessels and were helpful with salvage efforts. The primary function of tugboats was to help tow and guide ships into harbors, rivers, and ports. Larger ocean-going tugs were built to tow larger vessels or barges over long distances, with some towing across the Atlantic.

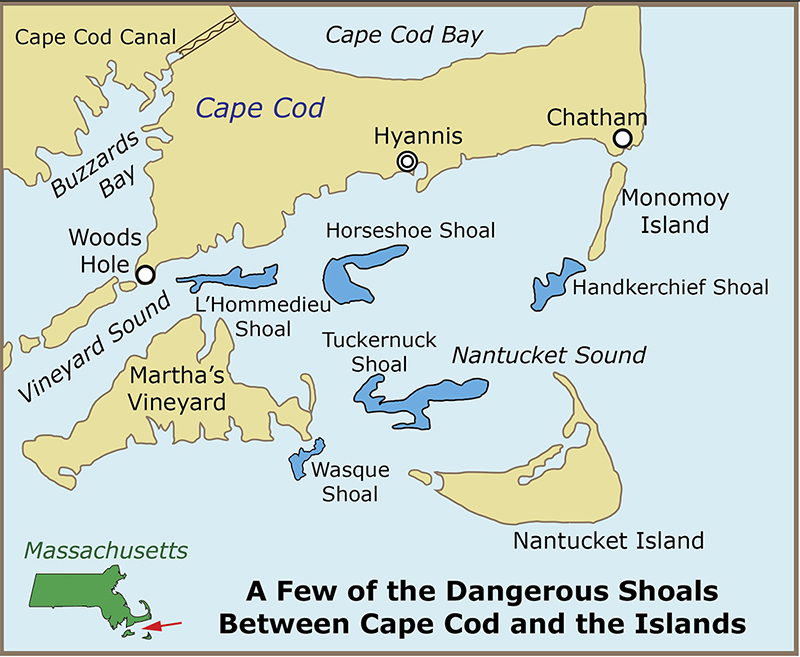

Due to the uncertainty of inclement weather up the Eastern Seaboard, and especially in the Northeast from New York through New England, most vessels involved in shipping would predominantly take the same shipping route. First, ships would pick up coal cargoes from the Mid-Atlantic states and sail through Long Island Sound in New York into Vineyard Sound off Massachusetts, between the great islands of Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket. Most vessels would take this route between New York and lower Cape Cod to avoid being caught in the open sea when fast-approaching storms came into New England. After rounding Cape Cod, these vessels would navigate around the rocky ledges and islands of Boston Harbor or continue to various ports up north along Maine’s rocky coast into Canada. They would also pick up timber and other cargo from the Northeast to bring south.

The Dangerous Shipping Route in the Northeast

The southern region along the Chesapeake Bay and within Vineyard Sound and Nantucket Sound in the Northeast provided a haven where ships could anchor in shallow waters over shoals while awaiting a storm. When fully loaded with cargo, many of these larger ships would have deep drafts, measured as the deepest portion of the vessel underwater. Mariners needed to be cautious in carrying such heavy loads to safely navigate around dangerous underwater shoals, sandbars, and reefs along this shipping route. During foggy or stormy weather, sometimes these ships would become grounded on these landforms, which could become a tragic event for the crew.

In the early 1900s, most merchant vessels were directly involved in shipping and deliveries during the harsh winter months of the Northeast and some Mid-Atlantic States. The Revenue Cutter Service began a more aggressive approach to surviving on the ice by breaking and clearing it. They began retrofitting existing steam-powered cutters around the Chesapeake Bay and up in the Northeast to serve in icy conditions where needed.

The Acushnet and the Androscoggin were two large, specialized cutters built for the Northeast in 1907 and 1908, respectively. The Androscoggin was designed and built in 1907 at Tompkins Cove, New York, to break the ice and keep open harbors all along New England in winter. It covered a substantial region of the New England coast, from Eastport in northern Maine down south to the southwestern shores of Massachusetts. The Androscoggin was the Revenue Cutter Service’s last boat built of wood at a length of 210 feet. At the time, some ship designers preferred wooden hulls to serve in icebound coastal waters.

The vessel had an iron-reinforced spoon bow and a powerful steam engine. It was the first American icebreaker designed to ride over the ice and crush it rather than backing and ramming, as with the steel-hulled steamers.

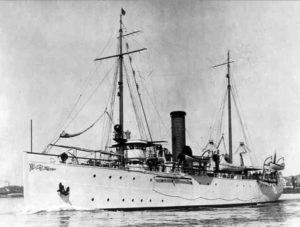

The heavily built steel-hulled Acushnet was constructed in 1908 by the Newport News Shipbuilding and Drydock Company in Virginia at 152 feet. The ship was robust enough to cruise New England in winter and break the ice with her reinforced steel hull and bow. She was stationed mainly at Woods Hole, near Nobska Lighthouse, in the Cape Cod region in Massachusetts, to work along Vineyard Sound and Nantucket Sound’s busiest and most dangerous shipping routes. The cutter became involved in the vast majority of rescues. This perilous region would have many ships grounding on the surrounding shoals or get caught up in the unpredictable storms that continued to raise havoc with mariners.

Revenue Cutter Achusnet out of Woods Hole, Massachusetts (Circa 1910). Postcard image courtesy Library of Congress

Congress finally merged the three service branches in 1915 into what we know as our current Coast Guard. For identification, the cutters’ initial lettering would be changed to USCGRC (U.S. Coast Guard Revenue Cutter) or USCGC (U.S. Coast Guard Cutter) before the ship’s name. The Coast Guard became essential throughout the Great War to protect American waters offshore and help deliver munitions and supplies along the East Coast.

Books to Explore

New England’s Haunted Lighthouses:

Ghostly Legends and Maritime Mysteries

Discover the mysteries of the haunted lighthouses of New England! Uncover ghostly tales of lingering keepers, victims of misfortune or local shipwrecks, lost souls, ghost ships, and more. Many of these accounts begin with actual historical events that later lead to unexplained incidents.

Immerse yourself in the tales associated with these iconic beacons!

The Rise and Demise of the Largest Sailing Ships:

Stories of the Six and Seven-Masted Coal Schooners of New England.

In the early 1900s, New England shipbuilders constructed the world’s largest sailing ships amid social and political reforms. These giants were the ten original six-masted coal schooners and one colossal seven-masted vessel, built to carry massive quantities of coal and building supplies and measured longer than a football field! This book, balanced with plenty of color and vintage images, showcases the historical accounts that followed these mighty ships. The first chapter involves the maritime history of the social and political changes that were going on in that period, as mentioned above.

Available also from bookstores in paperback, hardcover, and as an eBook for all devices.

Book – Lighthouses and Coastal Attractions in Southern New England: Connecticut, Rhode Island, Massachusetts

Lighthouses and Coastal Attractions of Southern New England:

Connecticut, Rhode Island, and Massachusetts

This book provides memorable human interest stories from each of the 92 lighthouses. You can explore plenty of indoor and outdoor coastal attractions, including whale-watching excursions, lighthouse tours, windjammer sailing tours, parks, museums, and even lighthouses where you can stay overnight. You’ll also find plenty of stories of hauntings around lighthouses.

Lighthouses and Coastal Attractions of Northern New England:

New Hampshire, Maine, and Vermont

This book provides memorable human interest stories from each of the 76 lighthouses. It also describes and provides contact info for plenty of indoor and outdoor coastal attractions and tours. These include whale watching, lighthouse tours, unique parks, museums, and lighthouses where you can stay overnight. There are also stories of haunted lighthouses in these regions.

Over 40 stories in my book New England Lighthouses: Famous Shipwrecks, Rescues & Other Tales. This image-rich book also contains vintage images provided by the Coast Guard and various organizations and paintings by six famous artists of the Coast Guard.

You can purchase this book and the lighthouse tourism books from the publisher Schiffer Books or in many fine bookstores such as Barnes and Noble.

Copyright © Allan Wood Photography; do not reproduce without permission. All rights reserved.

Join, Learn, and Support The American Lighthouse Foundation