Rhode Island’s Worst Maritime Disaster

Near Watch Hill Lighthouse, Rhode Island

The Collision of the Steamship Larchmont and the Schooner Harry P. Knowlton

New England winters are well known for their brutal stormy weather, and many mariners have become victims of its relentless storms over the years, especially where many storms came upon vessels with little warning. One of the worst disasters in Rhode Island’s maritime history involved the collision of the Larchmont and the Harry P Knowlton during a fierce winter storm.

Originally named the Cumberland, the Larchmont was over 250 feet long and known as one of her day’s finest side-wheel paddle-wheel steamers. She left a routine launch from Providence heading towards New York City at about 7 p.m. on February 11, 1907. Once past Point Judith Light, Rhode Island, Captain McVay left the responsibility to Pilot John L. Anson at the helm as he headed for bed. As the Larchmont headed west across Block Island Sound, a near gale-force wind was blowing, and as the vessel rounded Point Judith past Point Judith Lighthouse, the full effect of gale-force winds came upon her. The pilot pointed the paddle wheel steamer into the very heart of the gale and continued down through Block Island Sound as the weather worsened with snow squalls and poor visibility.

When the Larchmont reached about three miles from Westerly’s Watch Hill Lighthouse in Rhode Island, Pilot Anson noted that two sets of lights could be seen off the bow. It was the coal-laden schooner Harry P. Knowlton heading straight for the steamer. Several blasts were sounded on the steamer’s whistle as Pilot Anson and the quartermaster tried to veer the Larchmont away from the schooner to avoid collision.

Coastal seaweed covers rocks during low tide at Watch Hill lighthouse on an early summer evening in Rhode Island.

Before another warning signal could be sounded on the steamer’s whistle, the schooner crashed into the port side of the Larchmont just before 11 p.m. The noise of the crash awakened the sleeping passengers, followed by a loud explosion from the ship’s boilers. The impact of the schooner was more than half its length, which was forced over the breadth of the Larchmont. The severe turbulence of the sea then separated the vessels, and as the schooner slid away from the steamer, water rushed into the Larchmont’s gaping hole.

Most passengers on the Larchmont had previously retired for the night, and when the collision occurred, few were on board prepared for the freezing weather. Freezing in the cold, many rushed back below to secure more clothing. Others, barefooted and clad only in nightgowns, stood on the decks, fearing that to go below would mean certain death. These passengers became the majority of fatalities, freezing to death in the icy waters. Most died of exposure on an evening when the temperature had dropped to zero with a gale-force wind blowing against them. Even those few who were fully dressed and had later survived the ordeal endured extreme hypothermia and severe frostbite.

Every boat and raft sent from the Larchmont immediately headed for Fishers Point, the nearest landing point, which was still about five miles in the dark from where the steamer went down. Most boats and rafts became separated by the heavy winds and never made it ashore as most passengers and crew succumbed to exposure to the extreme cold.

Some of the passengers of the Larchmont were able to escape in lifeboats and made it to Block Island. Keeper Elam Littlefield and his family at Block Island North Lighthouse were awakened around daybreak by a 16-year-old survivor, Fred Hiergesell, who had managed enough strength to stumble up to the lighthouse from one of the lifeboats to get help. Keeper Littlefield alerted the local life-saving station and some fishermen to assist the frozen survivors. The lifesavers at the station rescued some survivors, and some by Block Island fishermen, who braved the stormy seas to try to save many from their frozen lifeboats and makeshift rafts.

Three island fishing boats, the Theresa, the Elsie, and the Clara E., sailed out from the island in search of other survivors at significant risk to themselves, as the seas were still very rough from the storm. About a mile from the shore, the crew of the Elsie found part of the hurricane deck of the Larchmont, with about 15 people appearing to be clinging on to it. As they got closer, they found about half had already perished, and those still alive were in terrible shape. Risking themselves in the still freezing temperatures and high winds, they were able to bring all eight survivors to their vessel and then brought them to the island to safety. Many of the Elsie crew also suffered from exposure to harsh elements. The island fishermen were awarded gold medals from the Carnegie Foundation for saving the survivors.

One man in one of the full lifeboats was unable to handle the extreme cold and, after watching those around him perish from the cold, went insane and slit his own throat to end his agony. The rescuers only found one survivor left from the boat, Oliver Janvier, a 21-year-old Providence man, who managed to make it to shore to tell the tale.

Captain McVey, providing his point of view when his lifeboat came ashore, gave most of the details of the terrible disaster. The captain later stated that it was shortly after 11 p.m. when his lifeboat was cut away from the sinking steamer, and it was not until 6:30 in the morning that it arrived at Fishers Point near Block Island to be rescued. None of the crew in the boat expected to survive the excruciating cold and icy water from the storm. The rescuers found that no one in the lifeboat was able to walk. Their feet were frozen so badly that the rescuers had to carry the survivors over their backs with their limp arms and legs to the life-saving station.

With a huge hole torn in her side, the steamer Larchmont was so seriously damaged that no attempt was made to bring the vessel ashore, as she sank to the bottom in less than half an hour. The 128-foot-long schooner Knowlton was carrying a load of 400 tons of coal and began to fill with water rapidly after she had backed away from the wreck. Still, her crew manned the pumps and kept her afloat until she reached a point off Weekapaug, where the men could get in their lifeboat and row ashore. The schooner had no fatalities, but the men suffered from severe hypothermia and frostbite from the extreme cold.

The next day, forty-eight bodies were found washed ashore, some frozen in the lifeboats and rafts. Many with their limbs and body parts frozen, broken apart and encased in ice. So many body parts were tossed ashore in such disarray that only six of the forty-eight bodies could be identified. Keeper Littlefield endured the grim task of retrieving the frozen bodies using his horse-drawn cart.

Aftermath and Investigation

Both captains, who survived, would blame one another for the tragedy. Capt. George McVey, of the Larchmont, declared that the Knowlton had suddenly swerved off from her course, was lifted in a monstrous sea swell by the gale force winds, and crashed into the steamer. Captain Haley of the Knowlton declared that the steamer did not give his vessel sufficient sea room and that the collision occurred before he could steer the schooner away from the path of the oncoming steamer.

During the formal investigation in the following days, Captain McVey claimed he was the last to leave his sinking ship. Those few surviving passengers disputed his claim, stating they observed the Captain and his crew as being in the first lifeboat, leaving the frantic passengers alone.

Primarily due to the freezing winter weather, over 143 perished, and only 19 survived, ten members of the crew and only nine passengers. The few who survived were in horrible conditions from the freezing temperatures and icy waters. After the investigation, the pilot Anson, who went down with the ship, was blamed for steering the Larchmont in the wrong direction when approaching the schooner Harry Knowlton. An official accounting of the Larchmont‘s passengers was never made since the list perished with the ship.

Although Watch Hill Lighthouse guided many vessels and their crews in fair and inclement weather, shipwrecks still occurred there. Unfortunately, two of the worst maritime disasters occurred near Watch Hill Lighthouse: the sinking of the Larchmont, as mentioned above, and the collision between the Nettie Cushing and the Metis. Years later, recommendations from the Larchmont’s disaster, and beforehand, after the tragedy of the Metis, established laws that required multiple lists of passengers and crew to be created and distributed between the vessel and on-shore destinations in case of further disasters. Out of many of New England’s shipwrecks and disasters, even though changes would take many years, many safety regulations were further established to help prevent or minimize these events and to help mariners, passengers, and family members of victims and survivors. Many of these changes are utilized today.

In memory of those who suffered or perished.

Allan Wood

Exploring Watch Hill Lighthouse

You can visit many specialty shops and restaurants on the beach, where you can park before walking to the lighthouse. Watch Hill Lighthouse grounds, which are open to visitors, and a small museum has been established in the oil house. The museum, which features a fourth-order Fresnel lens once used in the tower, is open during summer. You can walk along the stone seawall outside the grounds’ fence during low tide to get close views. Fishing offshore is a frequent pastime.

Here are some of my favorite photos of Watch Hill Lighthouse.

Books to Explore

New England’s Haunted Lighthouses:

Ghostly Legends and Maritime Mysteries

Discover the mysteries of New England’s haunted lighthouses! Uncover ghostly tales of lingering keepers, victims of misfortune or local shipwrecks, lost souls, ghost ships, and more. Many of these accounts begin with actual historical events that later lead to unexplained incidents.

Immerse yourself in the tales associated with these iconic beacons!

The Rise and Demise of the Largest Sailing Ships:

Stories of the Six and Seven-Masted Coal Schooners of New England.

In the early 1900s, New England shipbuilders constructed the world’s largest sailing ships amid social and political reforms. These giants were the ten original six-masted coal schooners and one colossal seven-masted vessel, built to carry massive quantities of coal and building supplies and measured longer than a football field! This self-published book, balanced with plenty of color and vintage images, showcases the historical accounts that followed these mighty ships.

Available also from bookstores in paperback, hardcover, and as an eBook for all devices.

Book – Lighthouses and Coastal Attractions in Southern New England: Connecticut, Rhode Island, Massachusetts

Lighthouses and Coastal Attractions of Southern New England:

Connecticut, Rhode Island, and Massachusetts.

This 300-page book provides memorable human interest stories from each of the 92 lighthouses, like the story of the Larchmont disaster near Watch Hill Light and Block Island North Light. You can explore plenty of indoor and outdoor coastal attractions, including whale-watching excursions, lighthouse tours, windjammer sailing tours, parks, museums, and even lighthouses where you can stay overnight. You’ll also find plenty of stories of hauntings around lighthouses.

Lighthouses and Coastal Attractions of Northern New England:

New Hampshire, Maine, and Vermont.

This 300-page book provides memorable human interest stories from each of the 76 lighthouses. It also describes and provides contact info for plenty of indoor and outdoor coastal attractions and tours. These include whale watching, lighthouse tours, unique parks, museums, and lighthouses where you can stay overnight. There are also stories of haunted lighthouses in these regions.

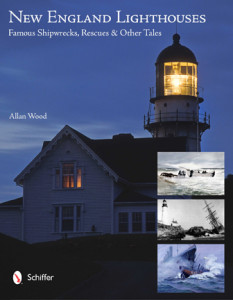

New England Lighthouses:

Famous Shipwrecks, Rescues & Other Tales

This book contains over 40 stories, including the Larchmont sinking between Watch Hill Light and Block Island North Light. It is also image-rich, with vintage images provided by the Coast Guard and various organizations and paintings by six famous Coast Guard artists.

You can purchase this book and the lighthouse tourism books from the publisher Schiffer Books or in many fine bookstores such as Barnes and Noble.

Join, Learn, and Support The American Lighthouse Foundation

Copyright © Allan Wood Photography; do not reproduce without permission. All rights reserved.